From Another Borderland

The problem is not how to get into the story, but how to get out of it. —Hayden White, Getting out of History, ‘Diacritics’ 1982

Rather, the imagination of cyborgs suggests a way out of the swamp of dualisms [...] —Donna Haraway, A Cyborg Manifesto, 1985

It would seem that after the history of the 20th century, the idea of shaping identity through a strict concept of nationality is becoming a thing of the past. However, history appears to be returning to the starting point, and the nation is still one of the strongest identity categories. Memory is an important factor in shaping attitudes in this area, and it is worth looking with a critical eye at those areas that have been repressed within it. When all other things are lost, traces of the past on the periphery are still preserved by architecture and natural witnesses—old trees or soil that hides mass graves.

I would describe the history of south-eastern Poland, where I grew up, as one such periphery, marked by the Holocaust, colonialism and ethnic tensions. On the other hand, the intercultural history of the region is sometimes carelessly described as an idyllic land where all religions and nations lived in harmony and peace. The shift of optics on the scale of micro-history[1] offers a way out of these misleading antinomies. The micro-histories of the pre WWII Polish-Ukrainian borderland offer an alternative concept of identity with its local, intercultural character that can not be closed in polarizing categories.

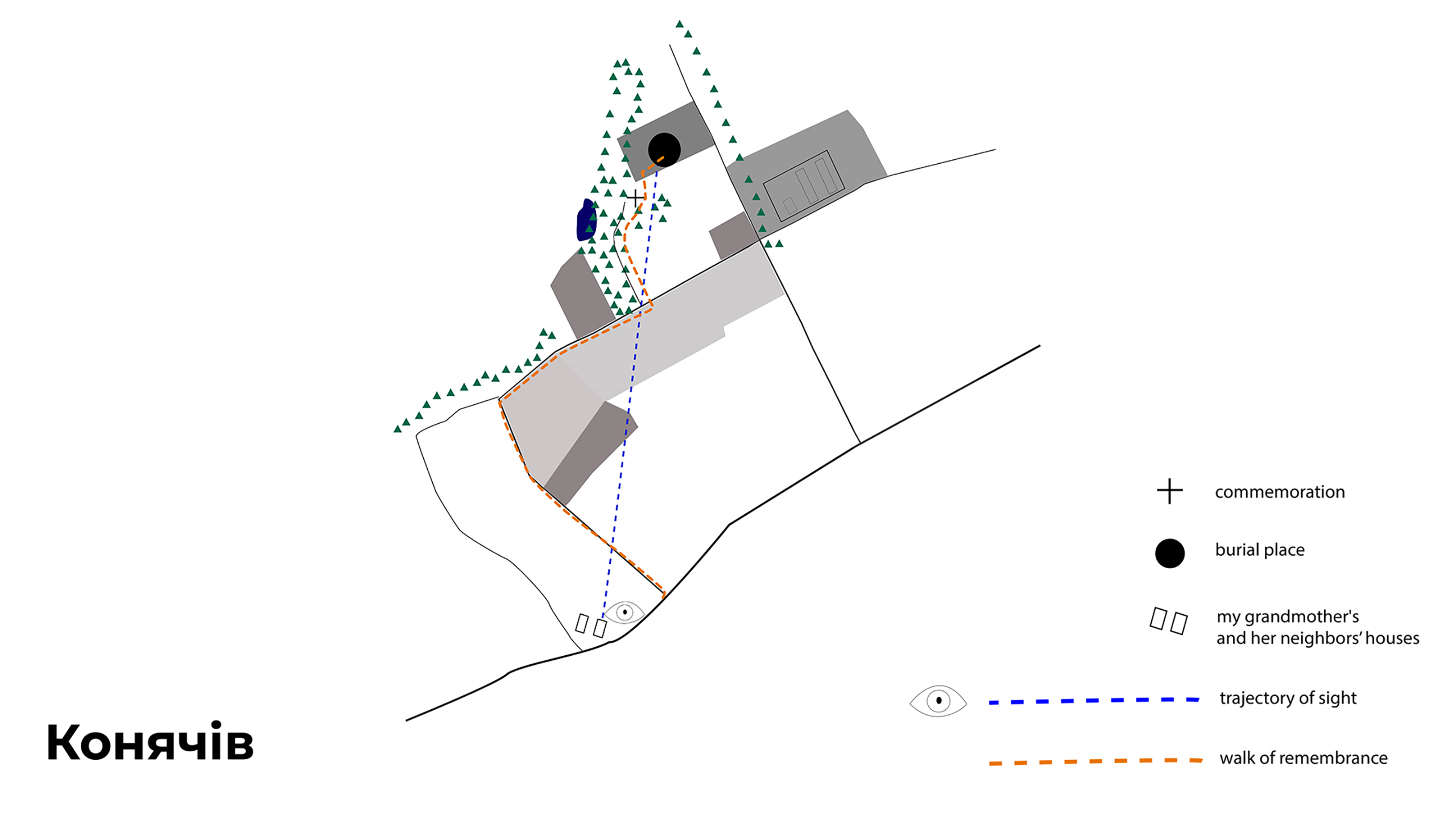

Koniaczów—Конячів

From our family home in Koniaczów, which is situated near a busy main road, you have to walk about a kilometer through fields and turn into a path through a grove of young pines to get to Mogiła [Eng. Grave]. On a winter afternoon, at the end of 2021, I went there with my dad for a walk of remembrance. Standing in the middle of a snow-covered farm field, he tells me what his mother, and my grandmother, told him about the place. Her name was Bronisława. During the Second World War and for the rest of her life, my grandmother lived in a small wooden house built in 1921. It was the last house in the village, closest to the farmlands. In 1944, from her attic window, she watched the smoke in the fields and the trucks going by. She was just over 20 years old at the time. My father recounts her testimony to me:

[…] there were observation points and the whole area was very clear. If someone was walking or driving, you could see it from far away and you couldn’t go near it. People of different nationalities were murdered here—from the round-ups, from the camp[2], and even children. […]And they brought naked people to this anti-tank hole, shot them, covered them with earth and lime, and only at the end of the war were they all burned to cover their tracks.

In the archives where I looked for confirmation of oral accounts,[3] Koniaczow comes up as a place where bodies are buried. This is also attested to by the Zapomniane Foundation, which reports on its website that about 3,000 victims (Poles and Jews) were murdered in Jarosław and burned in Koniaczów.[4] We do not know the names, exact number, or circumstances of the deaths of all the victims buried here. According to Martin Pollack, the victims’ anonymity itself became the final achievement of the murderers. He describes the multitude of such sites, especially in Eastern and Central Europe, as tainted landscapes.[5]

Despite intentions to cover their tracks, clods of earth still bear witness to the deaths of the people buried here. According to oral accounts, residents have long found items in the fields that may have belonged to the victims.

Claude Lanzmann called sites like this non-places of memory. In contrast to official commemorations, non-places constitute a second circuit—locations connected with death and genocide that have not been commemorated, although they influence local communities in various ways. For years, the attention of the discourse of memory has focused on the concentration camps in the best-known locations of the Holocaust, often overlooking the places of execution that were so numerous on the periphery. In almost every village there are places where blood was shed, but have nonetheless been pushed out of official circulation. Inhabitants of these tainted landscapes worked through the traumas of war in various ways. Their effect could be, for example, an increased religiosity in these areas, but it could also be found in the descriptions of places of execution as terrible, uncanny, or cursed.[6] My grandparents sometimes told of supernatural occurrences they had observed on the fields near Mogiła—such as children crying out of nowhere or strange behavior of birds.

According to Roma Sendyka, non-places of memory provide an outlet for the difficult past and the memory that does not fit into official narratives.[7] The space of non-memory in Poland is not only the unprocessed trauma of Nazi occupation. It is also an unworked heritage related to the Polish multicultural and colonial past. Podkarpacie, the landscape of my childhood, has long evoked in me the sense that there was someone else here—someone left behind by the void. Entire villages have sunken into the earth and their languages remain only on crumbling tombstones.

Next to my grandma’s house, there used to be another, very similar wooden cottage belonging to a neighboring Ukrainian family. Today, there is only one material trace left of the neighbors’ house—a table, which today still stands in the kitchen of my family home. The Ukrainian neighbors gave it to my grandmother on the day they left this place forever during Operation Vistula.[8] Like other families in the neighborhood, they were expelled as part of the forced resettlement of people that completed the Polonization of the area in the late 1940s.

An important issue I observe in the culture of remembrance in southeastern Poland, is the clear silent absence of Jews and Ukrainians who, before World War II, lived in this area. Despite the fact that they formed the local culture before the war, I observe a distinct lack in the representation of these groups in the contemporary culture of memory in the periphery. The San, which flows by just west of Koniaczów, is the biggest river in the Podkarpacie region. Before 1939, the Ukrainian population was the numerical majority on the eastern side of the river, while the further west one went, the more Polish-speaking the population became.

Although it is not obvious today, my home village Koniaczów [in Ukrainian Конячів] was also inhabited mostly by Ukrainian-speakers. According to the 1881 census[9] the village had a population of 240, of which only 17 were Roman Catholics (the traditional religion of the Polish population) while 223 were Greek Catholics (the religion of the local Ukrainian population). Today this place is inhabited exclusively by Poles. Apart from accounts of oral history, there is almost no trace of the Ukrainians who lived here before. The Ukrainian history of the place has almost totally vanished in the contemporary life of the village.

Oleszyce—ОЛЕШИЧІ

There are many more places here with similar histories. Driving further north from Koniaczów, I reach Oleszyce, where in the middle of a small town stands the abandoned Greek-catholic church from the 1920s. It looks like a festering wound in the middle of the town square. The grass in the church garden is freshly mowed. I decide to take a look inside. I manage to do so despite the closed door—there is a large hole in one of the walls of the church, through which you can freely enter. Inside there are rubble and remains of polychrome wall paintings.

A little further on, in Stare Oleszyce, there is another destroyed Greek-catholic church. To enter it, you need to talk to the parish priest. An older, polite man gives me the key and after a while, I find myself inside the building, which is threatening to collapse. It is surrounded by an abandoned cemetery and gravestone crosses. There are also the ruins of a historic bell tower. Only one of the gravestones looks new. A candle burns on it.

The walls of the temple inside are covered with quite well-preserved decorations. The polychrome mural in the center of the dome shows the Eye of Providence inscribed in a yellow triangle. From its very pupil, there is a metal cable, perhaps a trace of a former lighting system. The lack of glass in the windows has resulted in the deteriorating condition of the building year after year. The walls of the church are decorated with paintings that combine religious and folk themes. Among the colors of the whole church, shades of blue and yellow predominate. The ornamentation is far from that typically seen in Catholic churches—these are not floral rocailles, but rather folk embroidery-like geometric patterns. On the walls of the side nave, there are scenes of peasant life. On one of them, we can see two oxen harnessed to the plow. They are followed by a man in a white shirt, praying while working on a field. The lighting is tearing the sky apart. The whole picture is also painted in a yellow-blue color scheme. The author’s initials and the date are written in the lower right corner: ‘AX 1930’.

In the records of oral history from Nadsanie,[10] it becomes clear that the religious boundaries between the Polish and Ukrainian rural populations of these areas were naturally blurred for a long time. The local Ukrainian Greek-Catholic church may have been an organism much closer to rural society than the Catholic church—membership did not involve high fees and the churches were often located closer to the village community. This is particularly evident in the interior decoration of Ukrainian churches where scenes from the daily life of peasants are much more common.

There are many more such abandoned Greek-catholic churches in the region. During the communist era in Poland they were often used as warehouses, and to this day they fall further into ruin every year. Some of the temples have also been converted into Roman Catholic churches.

Multidirectional Memory

The history of Polish-Ukrainian relations is linked to Poland’s colonial past, exploitation and long-lasting conflict. A bloody war in the 1940s ended with Operation Vistula, an ethnic cleansing during which thousands of Ukrainians were expelled from southeastern Poland.[11] All these events, preceded by the Holocaust, led to the homogenization of the region’s population, which has since been inhabited mainly by Poles.

However, intercultural relations between the rural population cannot be reduced to these problems alone. Nevertheless, the attention of official commemorations of Polish-Ukrainian relations in recent years has focused mainly on ethnic conflicts. When analyzing contemporary local commemorations dealing with the issues of Polish-Ukrainian relations, one can get the impression that they present them from the dominant national perspective in a spirit of rivalry. Not only the content but also the form of the monuments, emphasize the domination of national symbols. The official narrative is written from the perspective of a homogeneous state, and ignores the specific relations between people who lived here before the war.[12]

Michael Rothberg’s concept of multidirectional memory[13] may offer a response to the homogenous culture of memory. According to Rothberg, national narratives are indicative of a zero-sum rivalry. In this kind of logic, the commemoration of one history removes the other from view. The model of multidirectional memory is a proposal in which the significance of historical events that support a great national history recedes into the background, and the struggle for the primacy of one history over another becomes irrelevant. By removing the category of the nation from the field of historical negotiation, Rothberg breaks the simple correlation between memory and national identity. He proposes instead a conception of memory as a continuous and multi-vocal negotiation between different groups.

By breaking the straight line between memory and identity built on national belonging, Rothberg denies the existence of separate identities defined by nationality, and, consequently, opposes a simple polarization.

The idea of multidirectional memory proposes the notion of identity as a dynamic process of continuous becoming and the creation of new forms of solidarity with others. Following this line, telling the story of one group or individual not only does not remove other instances or communities from view but also contributes to expanding the multi-directionality and dynamism of memory discourse, allowing it to transcend difficult histories. In the context of southeastern Poland, the stories of Poles, Jews, Ukrainians, Lemkos and their cultural and religious circles meet. Rothberg shows that it is possible not to treat them only through the prism of warring nationalities and that their voices need not compete with each other. Moreover, in Rothberg’s conception of memory, it is not possible to establish a ‘single, true version of history’ that will constitute an objective truth given once and for all. Multidirectional memory relies on the inevitable displacements and contingencies that characterize all remembrance. However, this is not a concept satisfied with pure pluralism alone—memory involves not only a multiplicity of voices but also an intensity of clashing social and political forces.

According to that—and bearing in mind the current war situation in Ukraine—the vision of a dynamic and contemporary-sensitive culture of memory requires it to be directed towards building relationships in the Polish-Ukrainian borderland. Dealing with the historical relations and politics of remembrance, we need to stop focusing on the warring national antinomies and find those micro-histories of shared neighborhoods that show how closely related these cultures were in local, especially rural communities. This can save us from creating more simplifying and totalizing systems that are misleading.

Neighborhood is a type of relationship that can form much closer ties than national affiliation. It should be taken into account that pre-war villages were much less connected among themselves than they are today. This meant that communities in each village had to rely on close relationships. For this reason, displacement and ethnic cleansing must have been very traumatic for the residents of these rural areas. At the same time, people had to deal with them on their own. My grandmother was born Polish in a Ukrainian village and died in a village that was entirely Polonized. When she was alive, she often recounted her experiences, although there were not many people willing to listen to her. Nevertheless, her testimony has survived, as has the gift she received from her Ukrainian neighbors—a large oak table.

One of my works in which I directly relate to my grandmother’s herstory, which I learned about during my walk to Mogiła, is Chernozem [Black Ground Carpet]. It is a carpet woven from dyed yarn, which refers to one of the most fertile soils found in some areas of southeastern Poland and Ukraine. For my grandmother, who was a farmer, the soil was a natural witness to the events of World War II and a silent confidant of memory. Combining the symbolism of home space and earth I point to the unprocessed traumas of war, genocide and ethnic cleansing which over the years destructively affect social and family relations especially in rural areas. In both collective and personal memory, these events are often repressed and literally “swept under the rug.”

The polarization and closure of the concept of identity is a result of 20th century totalitarianisms[11], and this process also takes place in the sphere of memory. However, the breakdown of totalizing and closed notions of identity is made possible by the micro-histories still present in (non)memory. The change of optics to the micro-level makes it possible to see halftones that cannot be seen from the perspective of great histories written in the service of national narratives. The micro-histories of the borderland show that the use of closing and divisive categories in the local, multilinguistic and multiethnic structures is (or leads to) cultural violence. Just as much as the silence about the memory of intercultural coexistence, even if it is not an idyllic picture, but a tension-filled, constantly negotiable legacy.

Magdalena Ciemierkiewicz was born in 1992 in Rzeszow, Poland. She lives and works in Warsaw. In 2016 she graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw at the Faculty of Painting. She is particularly interested in exploring the memory culture and micro-history of southeastern Poland, where she is from. She uses various media, including fabric, collage, video and sound.

Published 3 March 2023

- Ewa Domańska, Mikrohistorie, Spotkania w międzyświatach, Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, Poznań 2005

- a nearby Nazi concentration camp in Pełkinie, footnote by the author

- IPN Archive, IPN BU 2448/852

- Zapomniane Foundation’s mission is to search for, locate, study and commemorate the forgotten graves of the Holocaust victims. [acces:10-29-2022] https://zapomniane.org/en/miejsce/jaroslaw-2/

- Martin Pollack, Skażone Krajobrazy, Wydawnictwo Czarne, 2014

- Roma Sendyka Miejsca, które straszą, w: Poza obozem. Nie-miejsca pamięci. Próba rozpoznania, IBL, 2021, s. 153

- R. Sendyka, M. Kobielska, J. Muchowski, A. Szczepan, Nie-miejsca pamięci 1 Nekrotopografie, Instytut Badań Literackich, Warszawa 2020

- https://cis.mit.edu/sites/default/files/documents/ToResolveTheUkrainianQuestion.pdf

- Słownik geograficzny Królestwa Polskiego.—Warszawa: 1883—Т. IV.—S. 329.

- I used my own oral history recordings and recordings by Bogdan Huk, www.apokryfruski.pl [acces: 10-30-2022].

- T. Snyder, Rekonstrukcja narodów : Polska, Ukraina, Litwa i Białoruś 1569-1999, przeł. Magda Pietrzak – Merta, Wydawnictwo Pogranicze, Sejny 2006

- One of the objects that fit in this pattern is the monument located on the route from Koniaczów to Oleszyce. The main vertical element of the design is a concrete obelisk about 10 meters high, painted in white and red stripes.

- Michael Rothberg, Multidirectional Memory. Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization, 2009