Ghosts in the Blockchain, Wires in the Steppe

On cyberwar, cybernetic behavior and open-source

And though I don’t need either Planck or Bernstein,

I’ve studied their works, not seeing sunshine

I’ll never forget you, I’ll come there once more

As soon as we crash the spine of our evil foe,

I hope, my dear city, that you understand

I’ll meet you again, when I’m back, in the end

~ Kateryna Yushchenko, ca. 1940s [1]

When, in 1962, upon his second visit to the USSR, pioneer of modern cybernetics Norbert Wiener, was asked to assess the state of computer technology in the Soviet Union, he reportedly concluded that while hardware solutions were somewhat more advanced in the United States, the development of automation theory was most definitely being led by the Soviets.[2] This epiphany apparently came to Wiener following a detour to the newly opened Institute of Cybernetics in Kyiv, where the Department of Automation and Programming was chaired by Kateryna Yushchenko, a maverick Ukrainian mathematician who had already achieved groundbreaking advancements in computational machine learning throughout the previous decade. Among the many accomplishments of the department during her tenure was an addressable computing language—the world’s first advanced algorithmic language and the first fundamental achievement of the Kyiv School of Programming. Referred to today by some as the Ukrainian Ada Lovelace, Yushchenko and her story are exemplary on many levels. It illuminates the various forms of epistemic injustice that have been faced by Ukrainian scientists and thinkers—the Stalinist rejection and ridicule of cybernetics (which the regime saw as a threat to Communist central planning), gender inequality and unwaged reproductive labor performed by women active in the field of science, and, perhaps most importantly, the historical erasure and appropriation of Ukrainian scientific input into the larger scheme of “Soviet cybernetics’’. Yushchenko’s story is relatively unknown in the West and often portrayed incompletely, which is hardly justifiable, considering that the first computer in continental Europe and the prototype of algorithmic language were created in Kyiv by Yushchenko and her comrades.[3]

Born in 1917 in Chyhyryn, the former capital of the Zaporizhian Cossacks, Yuschenko faced a very arduous start indeed, full of political obstacles and hardships. Yushchenko’s father, a geography teacher, was considered “a Ukrainian nationalist” by the Communist Party due to his teachings on the Cossacks’ anarchic history, about which he even allegedly lectured dressed in a vyshyvanka shirt. This led to his arrest, and her expulsion from Shevchenko University as a daughter of “enemies of the people (враг народа). Unable to reenroll in university in either Kyiv or Moscow, Yushchenko fled to Uzbekistan to attend the Uzbek State University in Samarkand, where she simultaneously worked in cotton fields and as a detonator in a coal mine, not to mention her service in a military plant producing gun parts for tanks. While there, she wrote many poems, including the one offered as an introduction to this essay, a haunting testimony and love letter to her hometown—a hopeful declaration by a person displaced by two regimes who nonetheless continued to fight, work and write. It wasn’t until the end of World War II that Yushchenko returned to Ukraine, where, under the guidance of Ukrainian mathematician Borys Hnedenko, she completed what would be the first PhD awarded to a woman in the USSR in the field of programming in 1950. Soon, she joined the progressive Kyivian Institute of Cybernetics led by Sergei Lebdev and Victor Glushkov, where, during 1948–51, on the premises of an old monastery on the southern outskirts of the city, thirty scientists developed MEOM, a small electronic computing machine (ukr: Мала електронна обчислювальна машина) and the first computer in continental Europe.

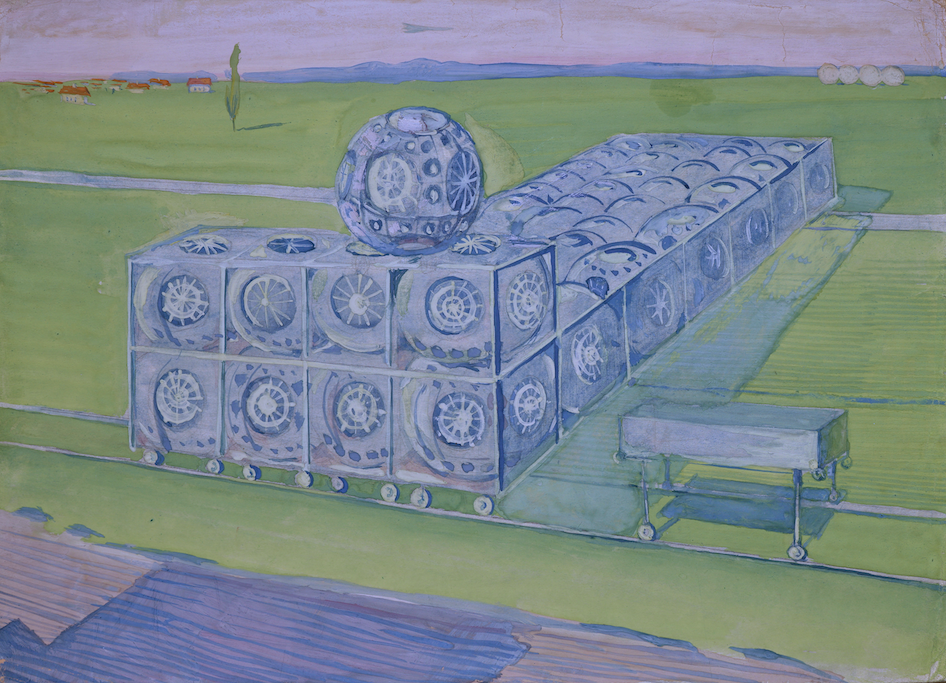

In this self-proclaimed exterritorial utopia, which the scientists unofficially gave the playful name Cybertonia, revolutionary thinking coexisted alongside a spirit of rebelliousness and dada-esque humor.[4] An addressable language for coding, database design and many other discoveries were made. Cybertonia issued its own humorous maps, stamps, passports and constitution, imagining a cyber-nation that was independent from the Soviet Union.[5] As media scholar Benjamin Peters writes, “a sense of collaborative, dedicated work ethic lingered in the decades thereafter, and a sense of local autonomy that was away from the watchful eyes of Moscow.”[6] This in itself was no small accomplishment, due to the fact that Soviet bureaucracy in the Stalinist period viewed the field of cybernetics with great suspicion and distrust. And while Kyiv’s cyberneticists had begun to develop algorithms and programs to solve problems of thermonuclear processes, space flight and long-distance transmission as early as the 1950s, their scientific and academic efforts were often suspended in space and time, oscillating between Stalinist censorship and the CoCom technology embargo from the West. Stalinists “excommunicated cybernetics as one of the worst bourgeois deviations”, Fredrick Kittler observes in Media Wars.[7] Behind this negligence and intimidation, which only began to thaw with Khrushchev’s takeover, was a fear of the conceptual framework that cybernetics offered: an autonomous, self-organizing system which could threaten top-down single-party rule. It suffices to think of Cybertonia’s co-founder Viktor Glushkov, who proposed the All-State Automated System of Management—a decentralized network, sometimes referred to (albeit in a clickbait manner) as the unrealized “Soviet Internet”. His decentralized project was envisioned to manage information flows among thousands of workers, but unsurprisingly it did not find the approval of the Politburo and never saw the light of day.

The distant echo of Cybertonia and Kateryna Yushchenko recently returned to me in an uncanny feedback loop, in light of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. What do decentralization and technological progress mean in the situation of war, a war that is shaped both by military and cyber warfare? Today, in the era of blockchain, social media activism and ungovernable complexities, we tend to think about decentralized networks as a panacea to digital feudalism and colonialism. But as McKenzie Wark suggests in her text “Vector and Territory”, perhaps, rather than thinking of every technology as inherently political, it may be more useful to think of every form of practicing politics as inherently technical.[8] This is why Cybertonias sometimes evolve into communities of startups and extraterritorial tax havens. Under different circumstances they also morph into self-organizing groups providing humanitarian aid, and into complex behaviors of grassroots networks which self-regulate without top-down authority. In this text, I would like to offer some thoughts on how various patterns of decentralization, transparency and sovereignty are articulated in the current military landscape.

Necrodigital disposability

Recently, in an attempt to navigate through the ‘Westplainatory’ news outlets, I embarked on an article on the American business channel CNBC, conspicuously titled “Eastern Europe created its own Silicon Valley. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine risks it all”. What struck me about this headline was how the very issues of agency, subjecthood and power apparatus were articulated. Exactly who created this sphere of influence known as ‘Silicon Valley in Eastern Europe’ and who will bear the sacrifice—the extractivist West known for its outsourcing services, or the thousands of IT workers, many of whom are now deployed on the battlefield? What does it tell us about global supply chains and labor relations under digital capitalism? I was, of course, aware of various outsourcing practices executed in the IT field in Eastern Europe which had accelerated over the course of the last two decades. Notably, I learned this lesson one particular day, twelve years ago when I boarded a plane with dozens of Polish, Belarusian and Ukrainian programmers on their way to an IT conference in Reykjavik. There, a fellow passenger, a drunk English tech dude, overjoyously mansplained to me that my Polish countrymen and other Slavs onboard have come a long way in their class mobility adventure. In his words, our mobile and disposable bodies belonged no longer to the best gastarbeiters, plumbers and sex workers in business; it turned out that we had also developed another niche skillset, or what the CNBC article described as a “talent pool”: “Unlike the economic hubs that have developed across the globe based on natural resource riches, precious minerals or commodities for fuel, intellectual concentration of resources doesn’t happen often. Before Eastern Europe, it had been decades since a significant new software and technology talent pool had been developed.”[9]

While reading this statement, I couldn’t help but think of Kateryna Yushchenko, who trained almost five generations of Ukrainian scientists and wrote a series of pedagogical manuals and textbooks. She supervised numerous PhDs in the field of programming, authored more than 200 academic texts, and yet, she was unable to prove her own talent in the eyes of the West due to the Cold War constraints and the lack of Western peer review in her academic circles. She stands as one of countless brilliant pedagogues in science, mathematics and astrophysics, who secured the position of Kyiv, Kharkiv and Lviv as top universities specializing in science and informatics. Today, under very different political and economic circumstances, many of these educational institutions, such as the National University Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, Lviv Polytechnic National University, the Igor Sikorsky National Technical University of Ukraine, and the Kyiv Polytechnic Institute have opened tech hubs, technoparks and innovation districts to nurture innovation in the local high-tech sector. But this situation did not happen overnight. With the crisis of the arms industry in the 1980s, a community of skilled engineers entered the market, and after the collapse of the Soviet Union their labor (by Western standards seriously underpaid) became available to the dot-com boom architects from the West.

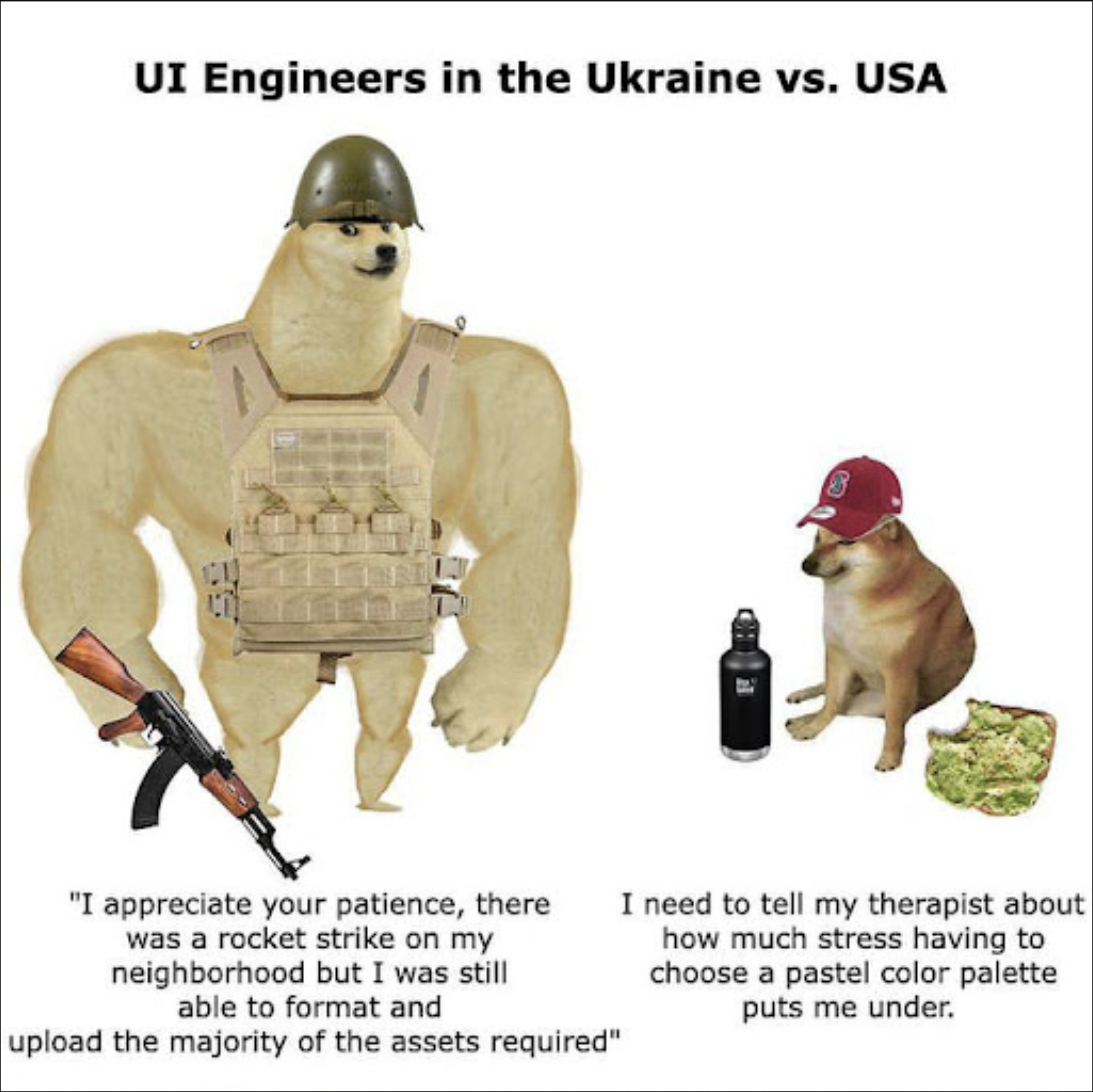

Although, thanks to radical digitization of governance and expansion of digital infrastructures, Ukraine today enjoys the status of one the most tech savvy countries in Europe. According to a Deutsche Welle report, 70% of Ukrainian engineers work as freelancers for Western companies, meaning “they have to deliver if they want to earn money and secure a follow-up contract.”[10] Tens of thousands of engineers working for outsourcing firms, regional startups and global tech giants have concentrated their activities in Kyiv and Kharkiv. Dutch software development outsourcing company Daxx, estimated that 200,000 Ukrainian IT developers were residing in Ukraine in 2020, while 20% of Fortune 500 companies have located their remote development teams there.[11] But what does this mean during wartime? While software firms with data secured in the cloud can easily relocate immaterial content regardless of whether Ukrainian urban infrastructure is destroyed or not, the labor of “the talent pool” (i.e. people displaced by the Russian invasion) continues to be deployed to keep cybercapital operating. This necrodigital disposability of humans performing work under military conflict was exemplified recently by one particularly nasty and dehumanizing meme that has been circulating on Instagram. The meme, executed in a reddit style, compares a maxxed out Swole Chad Dog wearing defense armour (Ukrainian IT specialist) and a Cheems dog with some avocado toast (presumably a programmer from the US), the first of whom remains working from a bomb shelter under inhumane conditions in order to provide digital services.

We can notice a double commodity fetishism here—the fetishism of the superhuman body restlessly working under military invasion and the fetishism of the memetic representation itself. For Marx, commodities are “magical” because capitalism obscures the conditions of labor, forms of privilege, and circumstances that underpin their creation.[12] Meanwhile, the crude meme conceals the “cultural-political” context and source of the image, allowing the viewer, unburdened by the gruesome realities of war, to focus exclusively on its humorous dimension as one of many memes consumed while scrolling and eating avocado toast. But the current invasion of Ukraine didn’t start on February 24, 2022, and neither did the extractivist practices that capitalize on the body and its ability to produce digital commodities through immaterial labor during war. Hito Steyerl’s video installation The Tower (2015) unpacks this subject from the perspective of the 2014 invasion of Donbas. The film’s protagonist, an aircraft engineer-cum-game developer working from Kharkiv (“1 km ride by tank’ from the Russian border”), describes his work of rendering commissions for Western companies that outsource the production of military simulations, online casinos, and real estate visualizations.

In her recent article “No Milk No Love”, Asia Bazdyrieva provided a deep analysis of the resourcification of Ukraine, a process which casts living and nonliving matter as inhuman resources and renders Ukraine “as an operational space, merely a site for material transaction”.[13] Elaborating further, she states: “The notion of the territory as a resource justifies a spatial organization that enables slow violence and environmental damage through the category of the inhuman. This process equates the human population and life at large to geological, agricultural, and other forms of matter with usable material capacities.”[14]

Following Bazdyrieva’s line of thought, we could say that the programming milieu and digital matter are also entangled in the extractive industries of contemporary capitalism, which sometimes mimic forms of extraction prevalent in the fossil fuel industry and agriculture, and sometimes create new models of resourcification emerging in data mining, AI development, algorithmic trading, etc. It is no coincidence that spaces for storage and data harvesting are often mediated through the rhetoric of agriculture—sites for cultivation of data, server farms, cryptocurrency silos and so on. Alongside raw materials (iron ore, steel, cast iron, grain, sunflower oil, etc.) which are sourced from Ukrainian land and held at Black Sea ports, a different type of extractivism emerges, hot and metabolic, transmitted through fiber optic cables and data centers. As capital seeks now to expand not only to the geological layers, oceans and to the cosmos, but also into atoms, cells and nerves, the extraction and depletion continue along new contours on the map where political, social, and technological networks mix with one another.

Take, for example, neon, an extremely rare gas that makes up only 18.2 parts per million in the atmosphere, but plays a crucial role in technology. It is used in the semiconductor industry by tech giants such as Intel, Texas Instruments and Samsung. The microchip in your phone and every electronic device that you use requires neon gas. As it happens, Ukraine produces an estimated 50 percent of the worldwide supply, and obtains it in a gas purification process, as a byproduct of steel manufacturing and metallurgical plants from the former Soviet era. The last time the semiconductor industry experienced a severe neon shortage was shortly after the Russian invasion of Crimea in 2014. The largest Ukrainian gas suppliers at that time, Cryoin and Iceblick, were located in Odesa, on the coast of Black. After the occupation, neon prices reportedly went up over 600 percent, global supply chains were compromised, and international microchip manufactures considered alternative locations of extraction in Asia. According to the US Trade commission, as a result of the current invasion, Cryoin, still based in Odesa, and Ingas, a neon gas company located in Mariupol, have been unable to continue production.[15]

From outsource to opensource

While the military invasion has put at risk Ukraine’s tangible reserves and resources, this war also occurs in the cloud and within the material infrastructures that underwrite it. An evident example of this are data centers—spaces for storage, passage and transmission of information. Although seemingly removed from our sight as abstract nodes of data architecture, these locations become objects of military warfare alongside other infrastructural targets of combat. According to the Data Center Map, there are 34 colocation data centers in 6 areas in Ukraine.[16] As one traces their positions in Kharkiv, Kyiv, Odesa, Khmelnytskyi, Mykolaiv and Vinnytsia, it becomes abundantly clear that their placements mirror the targets of attacks by the Russian missiles, where artillery has destroyed network cables in order to disrupt communications. At a tactical level, data centers play a crucial role as storage places of vulnerable assets, especially of data on citizens and government that in an emergency need to be moved to the cloud first before backup copies may be transferred to other storage places.

It is worth noting that Ukraine started to consolidate its governmental data in a Kyiv-based data center after Russia attacked Crimea and the Donbas region in 2014. This move towards centralization was done to prevent hostile takeovers and disruptions caused by cyberattacks. Furthermore, in 2021 the Ukrainian government prepared groundwork to construct a $700 million dollar data center close to the largest nuclear power plant in Europe, the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant (NPP), in order to host state documents and mine cryptocurrency.[17] But, as of March 2022, Russian have forces entered the territory of the nuclear power plant in Enerhodar, a satellite town of Zaporizhzhia NPP and continue to terrorize the plant staff and local inhabitants, in addition to compromising global nuclear safety at large. At the moment of writing, Russian troops control the administrative buildings and entry to the station while on Sunday, September 11, 2022 at 03:41 local time, power unit 6 of the Zaporizhzhia Power Plant was disconnected from the grid. Around 500 Russian military personnel remain at the Zaporizhzhia NPP, armed with large amounts of military equipment and explosives and using it as a nuclear shield. As stated on Energoatom’s website, the Russian military has also forced the power plant’s management to allow a well-known Russian blogger-propagandist with a Rosatom representative and armed soldiers into restricted areas including the control block of one of the nuclear power plant’s units.[18] There, they plan to organize filming and force Ukrainian personnel to participate in propaganda interviews, creating yet another myth for the Russian public. Consequently, as part of another Russian mystification, one of the mobile operators sent a fake mass-SMS to Ukrainian mobile numbers warning that the National Security and Defense Council had decided that Ukrainian operators should cease providing their services in the Zaporizhia region. These thermonuclear psyops are, of course, only two out of numerous examples of how military, cyber and visual codes of war mutate and interfere with one another. As Svitlana Matviyenko pointed out in the first weeks of the war, this invasion and the tension it produces “oscillates between two poles—AI and nuclear.”[19]

Given the interrupted plans to complete the ambitious Zaporizhzhia data centre and cryptocurrency mining facility by August 2022, it is impossible not to think of yet another layer of the current nuclear terrorism conducted by the enemy’s army—the assault on the cybersecurity and crypto-sovereignty of Ukraine, especially in the light of the virtual asset bill passed recently by President Volodymyr Zelensky. The bill regulates the country’s growing cryptocurrency market to provide Ukrainian citizens a safer and more regulated crypto environment. Since the outbreak of the war, cryptocurrency and the blockchain technology that support it have made possible some of the most significant forms of crowdfunding through Bitcoin and Ethereum donations, not to mention NFT (Non Fungible “Tokens” that can act as surrogates of specific assets) mining. But in the realities of cyberwar, blockchain, which facilitates transactions in a decentralized and encrypted way without middle men, can also advance the interests of dictators and terrorists for the evasion of sanctions, for example, which we have seen when Russia deployed cryptocurrency frauds eight years ago during the invasion of Donbas and Crimea. In a very interesting report entitled “The Separatist’s Guide to Circumventing Sanctions”, the Centre for Information Resilience, an open-source investigative agency, demonstrated how high-ranking pro-Russian individuals in the Donetsk People’s Republic avoided sanctions through cryptocurrency investment fraud, otherwise known as Ponzi schemes.[20] The key digital asset in this endeavor was Prizm, a cryptocurrency launched in 2017 by Russian politician Alexei Muratov, and advertised as the “‘first fair cryptocurrency’ with no central regulation or control, complete anonymity and absolute freedom from global financial authorities.” Incidentally, it also became the first cryptocurrency to be consecrated by a religious leader, as shown in the video below depicting a Russian priest spreading holy water on digital wallets.[21]

“The consecration of the Prism cryptocurrency by the priest Vsevolod”, uploaded 30 Jul 2019

Considering that blockchain tends to be equally fetishized and demonized in public debate, this may not be a good moment for self-congratulatory leftwing theorizing about the dangers of digital capitalism. Ultimately, what is important is how to help Ukraine win this war and what aspects of decentralized blockchain structures and open-source technology we should utilize to this end. Because blockchain is neither moral nor amoral, it can reproduce, reinforce or interrupt cycles of violence depending on the intentions and the nodes within the structure. Two specific use values strike me as particularly worthwhile: 1) the possibility it offers for encryption of war crime evidence, where each document is captured, encrypted and stored on a decentralized ledger, and 2) the use of agro tokens, which transform grain into a digital asset.[22] “Tokenized grain” which is essentially virtual money backed by tangible crops could prove a hopeful solution allowing Ukrainian farmers to store or exchange these tokens for seeds, tractors, machinery, fuel, services and other assets in light of the staggering sowing crisis and withholding of grain at the Black Sea ports. But implementing any technology takes time, and time itself is a risk asset.

Cybernetic behavior and palianytsia cryptography

It is tempting to think that the patterns of cyberwar are drawn along the lines of binary positions: transparency versus opacity, surveillance versus publicly available footage deployed to coordinate targeting, autocratic centralized systems of the Russian military command against decentralized networks of the Ukrainian army. As numerous programmers from Eastern Europe joined the IT army to conduct open source intelligence, ordinary citizens didn’t fall far behind. Think of the Ukrainian farmer who tracked stolen airpods via Apple’s Find My Phone app all the way to Central Russia, or the person who recognized their stolen fridge in a Russian propaganda video by noticing the insurance stamp on it issued by a Ukrainian wholesaler. Consider the territorial defense battalions where housing cooperatives have become the main units of self-organization or Ukrainian hackers impersonating attractive women to lure Russian soldiers into giving them location. Think of the Ukrainian army’s management style, which involves coordinating the activities of smaller units with a high degree of autonomy for lower-level commanders. What we have witnessed in the past months was a collective intelligence emerging through interrelated connections and relationships not only on Telegram chats, Facebook groups and other social media outlets, but through an analogue network of gestures, tears and hormones. This is why, when considering transparency, encryption, and autonomous networks of exchange, we should note that the most crucial cybernetic knowledge is performed by bodies via grassroots civic efforts, which are enmeshed together in delicate nets of support. This type of messy block/chain of entanglement is performed not just to flourish and prosper in speculative crypto bubbles, but in order to resist, survive and offer mutual aid. In a state of war, direct cybernetic action means deciphering endless configurations of escape routes, obscuring intentions, the direction or speed of the enemy, etc. But it also means coding behaviors through body and language, for example by identifying Russian saboteurs with the word palianytsia, a famously distinct Ukrainian word that stands for wheat bread. Because ultimately it is the body that transmits these codes, and it is the body that inhabits algorithmic thinking, responding with crisis-specific permutations.

Natalia Sielewicz is an art historian and curator at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. In her exhibitions and essays, she addresses the issues of feminism, affect culture, biopolitics, and technology. The curator of the exhibitions: Fedir Tetyanych. The Neverending Eye (2022), The Dark Arts. Aleksandra Waliszewska and Symbolism of the East and North (2022, co-curated together with Alison Gingeras), Agnieszka Polska. The One-Thousand Year Plan (2021), Paint also known as Blood. Women, Affect, and Desire in Contemporary Painting (2019), Hoolifemmes (2017), an exhibition problematizing performativity and dance as tools of female resistance, the exhibition Ministry of Internal Affairs. Intimacy as Text (2017) on affect and the poetics of confession in literature and visual arts. She also curated Private Settings (2014), one of the first institutional exhibitions examining the impact of Internet 2.0 on the human condition in the age of late capitalism, and the exhibition Bread and Roses. Artists and the Class Divide (2015, with Łukasz Ronduda). She is part of the Sunflower Solidarity Center at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw.

Published 31 October 2022

- A poem-letter to the city of Chyhyryn by Ukrainian computer scientist and cybernetic polymath, Kateryna Yushchenko, ca. 1940s https://habr.com/en/company/ua-hosting/blog/387837/ quoted in English : https://medium.com/a-computer-of-ones-own/kateryna-l-yushchenko-inventor-of-pointers-6f2796fa1798

- This anecdote was told by Yuriy Yushchenko, scientist and Kateryna Yushchenko’s son in an interview for DOU.ua, the biggest website for the programmist and tech developers milieu in Ukraine. Eleonora Burdina, Stvoryla odnu z pershyx u sviti vysokorivnevyx mov prohramuvannya. Istoriya ukrayins”koyi naukovyci Kateryny Yushhenko, 7.09.2019, https://dou.ua/lenta/interviews/about-kateryna-yushchenko/ [accessed: 1.07.2022]

- Additional information on the Kyiv Institute of Cybernetics and Kateryna Yuschenko (based on her memoirs) can be found in B.M. Malinovsky, Vidome i nevidome v istoriyi informacijnyx texnolohij v Ukrayini, Kyiv, “Interlink”, 2004. Online resource: International Charity Foundation for History and Development of Computer Science and Technique, History of the development of information technologies in Ukraine http://www.icfcst.kiev.ua/MUSEUM/Ushchenko-memoirs_u.html [accessed: 1.07.2022] It is worth noting that her Address Programming Language, developed in 1955, preceded other famous programming languages, such as FORTRAN (1958), COBOL (1959), and ALGOL (1960).

- Please see Benjamin Peters, How Not to Network a Nation: The Uneasy History of the Soviet Internet, Cambridge, MA : MIT Press, 2015.

- Ibid.p. 131

- Ibid. P. 128

- Friedrich Kittler, “Media Wars”, Literature, Media, Information Systems, Routledge: London, p. 128

- McKenzie Wark, “Vector and Territory”, presented at Electric Summer School, Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, 23.07.2021. https://vimeo.com/578387103 [ accessed 25.07.2022]

- Eric Rosenbaum, “Eastern Europe created its own Silicon Valley. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine risks it all”, CNBC, 5.03.2022, https://www.cnbc.com/2022/03/05/the-eastern-european-silicon-valley-boom-in-the-middle-of-russias-war.html [accessed 1.07.2022]

- Tatjana Schweizer, “Eastern European IT specialists caught in the crossfire of war”, Deutsche Welle, 16.03.2022 https://www.dw.com/en/eastern-european-it-specialists-caught-in-the-crossfire-of-war/a-61139248 [accessed 1.07.2022]

- Rosenbaum, ibid.

- Phillips, Whitney, and Ryan M. Milner. The Ambivalent Internet: Mischief, Oddity, and Antagonism Online. John Wiley & Sons, 2018. Ebook. p. 195

- Asia Bazdyrieva, “No Milk, No Love’, E-flux Journal, Issue #127, May 2022, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/127/465214/no-milk-no-love/ [accessed 15.06.2022]

- Ibid.

- U.S. International Trade Commission Executive Briefings on Trade, April 2022 Ukraine, Neon, and Semiconductors, https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/executive_briefings/ebot_decarlo_goodman_ukraine_neon_and_semiconductors.pdf

- https://www.datacentermap.com/ukraine/

- Sebastian Moss, Ukraine plans huge cryptocurrency mining data centers next nuclear power plants. 1.02.2021 Data Center Dynamics https://www.datacenterdynamics.com/en/news/ukraine-plans-huge-cryptocurrency-mining-data-centers-net-nuclear-power-plants/

- https://www.energoatom.com.ua/o-1007221.html

- Svitlana Matviyenko, “Dispatches from the Place of Imminence, Part 3,” Institute of Network Cultures, March 5, 2022, https://networkcultures.org/blog/2022/03/05/dispatches-from-the-place-of-imminence-by-svitlana-matviyenko-part-3/

- https://www.info-res.org/post/report-the-separatist-s-guide-to-circumventing-sanctions

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PXRcit1SMBM

- Recently Starling Lab, an academic research center co-founded by Stanford University’s department of Electrical Engineering and the USC Shoah Foundation, has submitted a cryptographic dossier, documenting possible war crimes in Kharkiv to the the International Criminal Court. Their digital evidence package is preserved on 7 protocols across decentralized web. As per agro tokens, it is a solution currently offered by Santander Bank in Argentina. I managed to establish that Ukrainian company Pembrock Finance, Ukrainian offers leveraged yield farming application on open source technology NEAR Protocol.