The Tale of the Donetsk Roses

by Natasha Chyshasova

The concept of ‘Donrosa’, a utopian garden city plan of Donetsk, was developed by Pavlo Makov and turned into an artwork and a book (2008-2010) by the same name. Based on ideas of British urban planners of the 1990s, Makov developed a myth of the history of the Donrosa garden. In this essay, curator Natasha Chychasova analyses the Donetsk rose’s symbolic meaning has changed over the course of the region’s history – from a feature of industrialisation mythology to a symbol of local perseverance and hope.

Local legend has it that Donrosa had been proposed, or even perhaps existed as a design, from the late 1900s, created by gardeners from Great Britain, and commissioned by local rose enthusiasts and collectors as a template for the future Great Eastern Botanical Garden. [1] From Pavlo Makov’s book Donrosa

The rose has so many layered meanings in world culture that it makes your head spin. Mankind has labelled the rose the ‘queen of all flowers’ and has invented a whole symbology for them: the red rose is a symbol of passionate love and even a symbol of revolution; the yellow stands for hope and friendship; the white for purity. But how did this flower get to Donetsk Oblast and how did it become one of the region’s symbols? My hometown of Donetsk, the regional capital, was known as the ‘city of a million roses’. For a long time this was an empty cliché for me. The beds of red flowers were the backdrop you passed on the street and you would never consider the question ‘why roses’. But, as is so often the case, questions only begin to emerge when you have nowhere to ask them. Since the rose is the queen of all flowers, her story is a fairy tale, from how she grew, to how she changed, and how she died and was reborn. I justify this form to myself by saying that when reality becomes impossible to comprehend, all stories become like fairy tales.

Chapter 1. IN PURSUIT OF BLACK GOLD

In ancient times (more precisely in the 16th and 17th centuries), there was a land called the Wild Fields. It was a vast steppe, a periphery and a place of conflict. Here Tatars paved trails (sakma), Cossacks built winter quarters and villages, and fugitives sought a better fate. There was a place for everyone. After these lands became part of the Russian Empire, the freedom of the steppe was interrupted. The Cossacks were destroyed, the people who lived here were forced into serfdom, and the steppe itself began to be developed. The empire needed not only labour, but also raw materials to strengthen its own military power, because it planned to advance further — to the Black Sea.

During the Crimean War (1853–1856), the empire felt the aging of its military complex and the lack of infrastructure particularly keenly. In his book Wild East. An Essay on the History and Present of Donbas, the journalist Maksym Vikhrov quotes the correspondence of a French soldier, in which he says: ‘They [Russian soldiers] have no grenades. Every morning their women and children go out into the open field between the fortifications and collect the grenades in sacks’ [2].

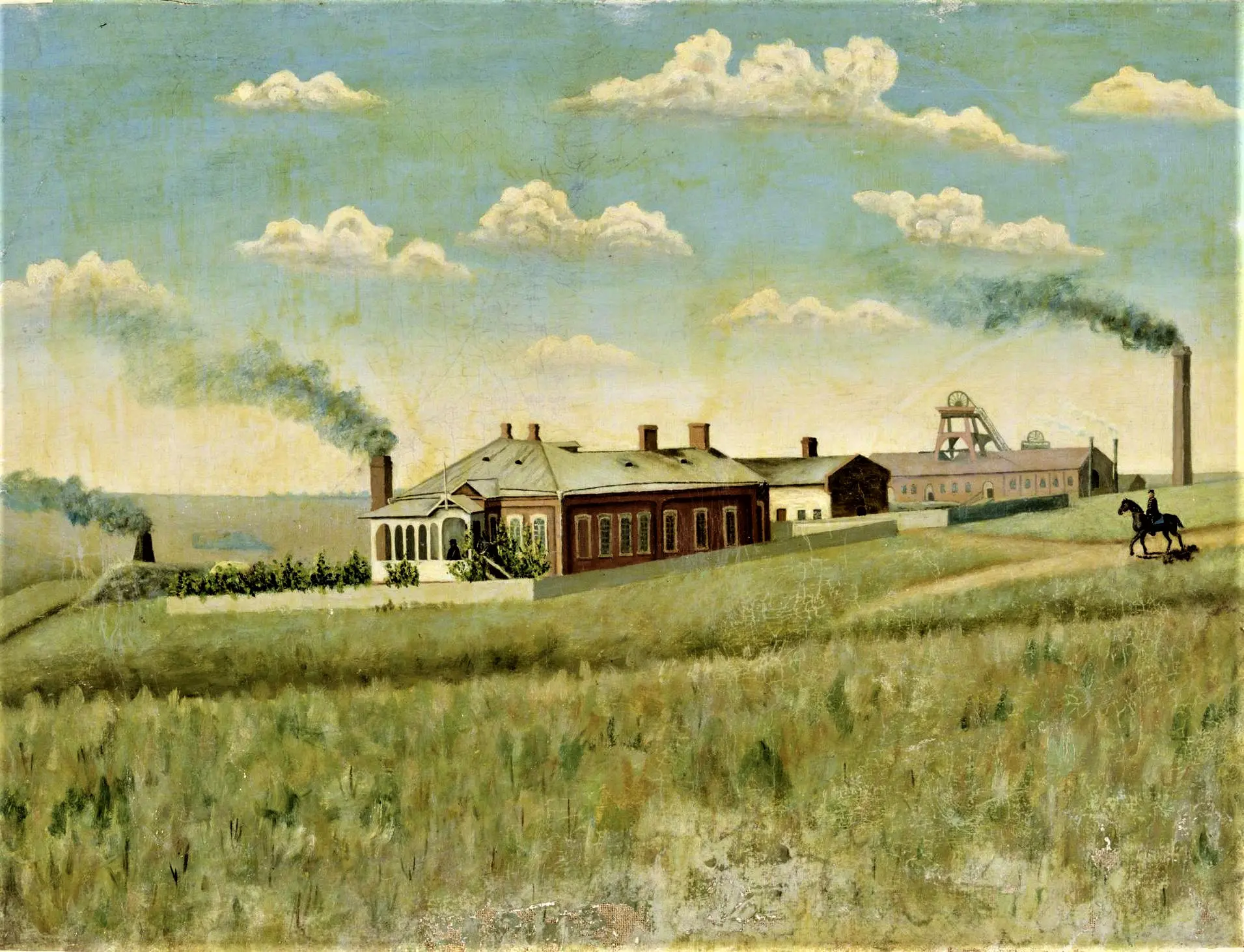

Despite the initial unsuccessful attempts by the Russian Empire, the plan to develop the Donbas was finally realised thanks to the involvement of foreigners and their capital. The Welshman John Hughes founded the Novorossiysk Coal, Iron & Railway Production Company, which, by the beginning of the 20th century, was becoming the leading steel producer in the Russian Empire. In these industrial times, coal and metal were the new gold, and the Donetsk coal basin was nicknamed the Black El Dorado [3]. From peasants workers to fugitives and prisoners, the mines were worked in by a tapestry of different people. The population of the Donbas consisted mainly of migrants from various parts of the Russian Empire who, according to researchers Volodymyr Kulikov and Iryna Sklokina, ‘were forced to form new communities based on professional needs and the practices of daily life’ [4].

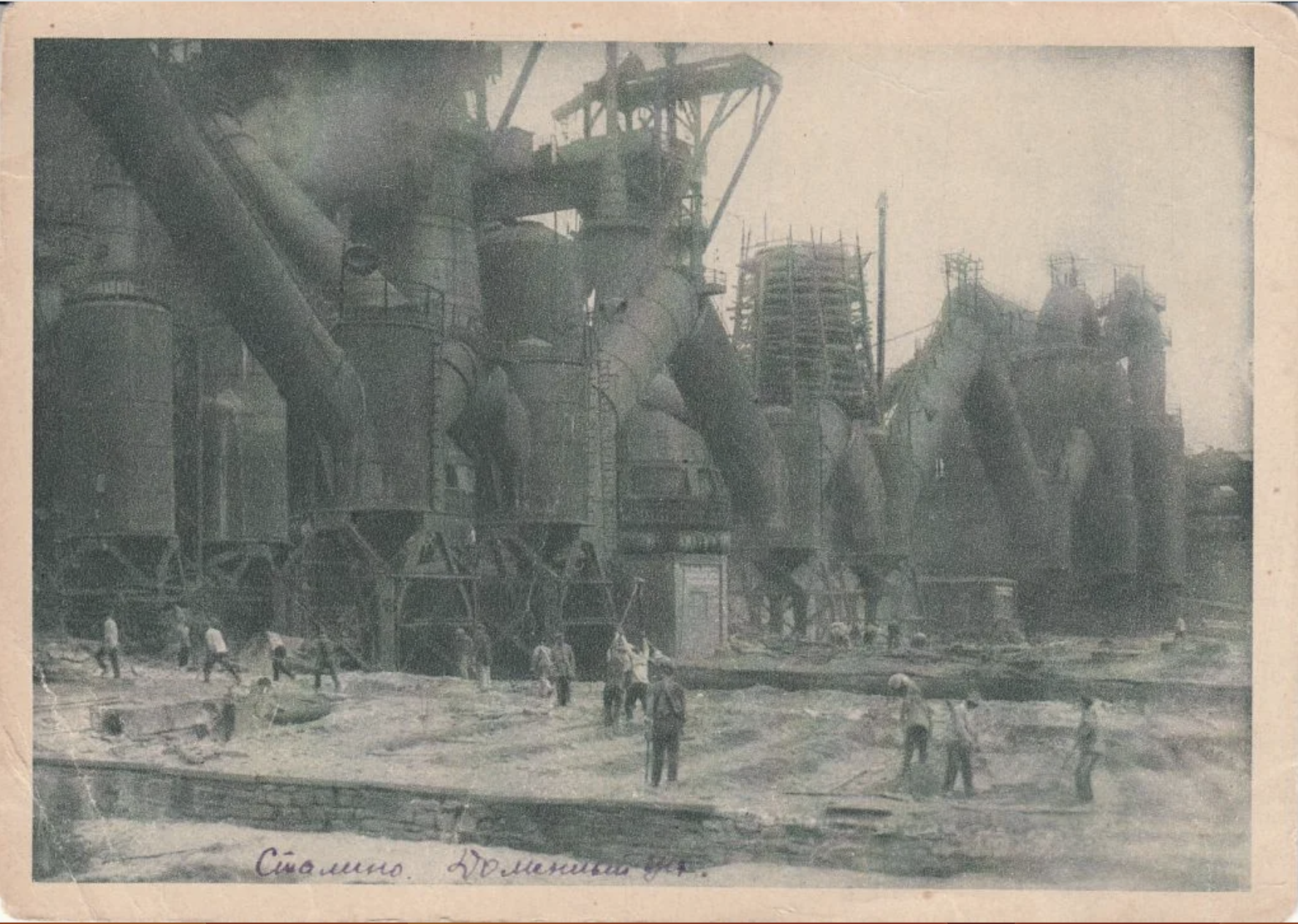

After the establishment of Soviet power and the increased repressions that came with this, the importance of the strategic project for the development of the industrial Donbas became even greater. Its aim was to become the embodiment of the Soviet idea, with developed cities, efficient enterprises and happy workers who would be diligent whilst having access to all benefits. This industrial utopia was affirmed in visual culture by the Soviet director of Jewish origin, Dzyga Vertov, in the first Soviet sound film Enthusiasm. Symphony of the Donbas (1930) [5]. Gradually, the former Wild Fields was transformed into a furnace, and all that remained of the boundless steppe was poisoned and depleted land. The Donbas was a grey place, smoky with black soot, where life was a real challenge. The Ukrainian writer Borys Antonenko-Davydovych left the following notes after a trip to the Donbas in 1929:

‘But where is Ukraine here, amidst this colorful desert landscape? Where is the steppe? It’s true, it’s there — “steppe and steppe alone without end”, but it’s bare, smoky, dusty. No former sawdust, no modern wheat and rye! A neglected, wasted steppe. Just there, and there, and a little further to the left — a black wheel of “colour” and the Cheops-like pyramids of terracotta… No, this isn’t the steppe I imagined as a child; it’s not even a degenerate descendant of the ancient Wild Fields and the pristine freedoms of the grassroots; it’s something completely different’ [6].

Thus the wealth of natural resources in this land became their curse. It was plundered and looted, and its hard-working people died. The land in the Donbas became more and more tired every day, as did its inhabitants — all of this contrary to official Soviet propaganda, which described it as an industrial, progressive paradise.

Chapter 2. HOW THE DONROSA CAME INTO BEING AND BLOSSOMED

Resources tend to exhaust themselves. The Soviet planned economy proved to be inefficient, and the mines and enterprises were in need of modernisation, which they mostly did not receive. To divert attention from the growing problems in the region, the authorities decided to take up landscaping. Moreover, this idea fitted in well with the general ideology of a superhuman conquering nature and being able to inhabit and live in the most unfavorable places for this place. The researcher Tetiana Portnova points out this was a part of the Soviet desire to implement a utopian project of synthesizing industrial and natural spaces [7]. The ideal was huge factories, near which gardens would blossom and nightingales would sing. Although the first plans to transform the cities of the Donbas into ‘garden cities’ – following the movement popular in England in the early 20th century and first conceptualised by Ebenezer Howard – were discussed in the 1920s, they only began being implemented in the 1950. The planting of flowers, especially roses, played a special role in this.

According to legend, it was the First Secretary of the Donetsk Regional Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, Volodymyr Dehtiariov, who first came up with the idea to make the rose a symbol of Donetsk in the 1960s. Thus, the first rose bushes began to appear in the city, which over time only gained momentum. Researcher Olena Taranenko [in her commentary to Radio Svoboda – Ed.] notes that by 1970s Donetsk was rapidly approaching a million inhabitants and that consequently the slogan appeared: ‘Let’s make Donetsk a city of a million roses; a rose bush for every resident of Donetsk’. This initiative justified itself and the rose quickly became a recognisable symbol of the city.

As the Soviet Union approached its ultimate collapse, it was no longer possible to hide the decline of industry. Donbas miners actively protested and put forward political demands, including fighting for the independence of Ukraine. Gradually, a combination of financial hardship and suppression by local elites forced the miners to end their protests in order to hold on to their jobs. For example, the last big protest of mine workers in Luhansk in 1998 was dispersed by Berkut special police forces, who beat the protesters and used tear gas. Subsidized enterprises and mines began to close and jobs became scarce. The towns that were built around the mines and enterprises – so-called monotowns – became increasingly depressed after their closure. However, the 1990s was also a time of ‘wild capitalism,’ which led to the rapid enrichment of local elites and the formation of oligarchic clans. For these local elites, Donetsk became an embodiment of the idea of wealth and prosperity, and they actively invested in it. Although in the early 1990s the rose tradition was lost, in the 2000s it returned again and took an important place in the mythology of the city, with equal importance to the Day of the Miner and Metallurgist, juxtaposing the beautiful with the industrial. This phenomenon can be seen as an attempt to find support from local elites and ordinary citizens alike through the emphasising of a symbol that highlighted the prosperity of the city and its wealth. It is no wonder that the city’s slogan for the Euro 2012 football championship was ‘Donetsk — Strength and Beauty,’ whilst its emblem combined graphic images of coal and a rose.

Between 2008 and 2010, Pavlo Makov produced the work Donrosa, a large etching print for his ‘Gardens’ series [8]. While working on it together with artist Gamlet Zinkivskyi, the Donrosa book was born [9]. In fact, this book was a master plan for a Donetsk rose garden, in which the utopian landscape of the city would be divided into sectors dotted with gardens of different varieties.

Makov himself once said, ‘Looking at the roses in Donetsk, I always thought that this was the blood of miners that came to the surface from underground’ [10].

Makov includes in Donrosa a phrase from Dante’s The Divine Comedy: ‘Abandon all hope, ye who enter here.’ As a teenager, I could never explain the meaning of this phrase as a characterisation of my city, as it seemed as though all around me things were blooming. I was so naive. For me, as well as the majority of Donetsk residents, the dark clouds were forming unnoticed.

In 2014, Donetsk was occupied by Russian military formations. News about the life of the city can now be learned only from occupation sources and publications by local residents. The desire of the occupation authorities to create the illusion of well-being in the city also led to their renewed interest in roses. ‘Even now, in conditions of war, attention to rose culture in the city landscaping is not weakening’ [11]. This propagation of roses thus serves as a facade to cover up the outflow of people and the decline of the city’s infrastructure, which with each year of occupation is becoming more and more ghostlike. Donetsk no longer has a million inhabitants, nor does it have a million roses.

Chapter 3. REBORN FROM BLOOD

Lately, my thoughts have been returning more and more to Pavlo Makov’s aforementioned phrase that a rose is blood that has come to the surface from under the ground. Perhaps legends do not lie and the flower that was once born from the blood of Aphrodite is drawn to her. It represents all those who built Donbas, worked in its depths and on the surface, all those who now stand on its defense. Now, looking at the rose bushes in the cities, I remember the Donetsk rose gardens and understand that they have never just been the background of my life. In her manifesto, the artist Kateryna Aliinyk, who herself comes from Luhansk, noted the following:

‘The inability to get closer to the landscape and interact with it turned into a realization of its greatness and a deep sense of respect. It turned out that my presence was powerless to influence the faith of this land, and my absence was just my personal tragedy. That is when I realized that landscape isn’t a background; it’s an action’ [12].

This impossibility of real proximity leads to a constant search for a meeting, and an attempt to approach what was lost in any way. The rose has remained an important symbol for all those who left and has come to personify hope. For example, in Irpin, people from Donetsk Oblast plant rose alleys in memory of their cities. In Pokrovsk, which is now [as of February 2025 – Ed.] a strategic target of the Russian offensive and for which fierce battles are being fought, people continued to plant rose beds in the city until it became impossible to continue to do so.

Halyna Fateieva, a resident of Pokrovsk, told journalists that ‘[t]he rose is like us: It has thorns and it protects itself, but it brings beauty into this world. […] My neighbors – and even strangers – say the roses refresh them and give them hope’ [13]. Pokrovsk also had one of the largest rose nurseries in Ukraine, Roses and Gardens of Donbas [14]. Its owner, Viktor Masiuk, did not abandon his business even after the full-scale invasion began and began a project, sending roses (which he called ‘roses of peace’) from his nursery all over Ukraine. Now, even when the nursery’s owners have been forced to leave their homes, their roses continue to live on across the country.

Likewise, Donetsk, which is no longer the city of roses, will remain a city of roses forever — for all those who lived there and loved it — as well as other cities that were completely destroyed or are under occupation. Although, to be completely honest, I do not believe that a fairy tale about the city of a million roses can have a happy ending. Horrible pictures and thoughts, like in a kaleidoscope, replace one another in my mind: the unique nature reserves of Kamiani Mohyly [Stone Graves] and the Khomutivskyi Steppe, burned and disfigured by craters; abandoned mines that fill with water and create terrible abysses; broken enterprises that release their toxic blood into the black soil; thousands of mines and shells hidden in fields and forest belts, bringing with them sudden and terrible death or mutilation. However, somewhere on the outskirts of my imagination, the dream of the Great Eastern Botanical Garden, which from being utopian, will one day bloom with millions of roses of various breeds, still haunts. It will not be a place of revival of the ‘former greatness’ of Donetsk, but rather a garden of sorrow. It will be a garden in which both all those who lived in the city during the occupation and all those who will return back home in memory of the dead and tortured, will plant a bush of red roses, and thus the Donrosa garden will be actualised.

Editing by Ada Wordsworth.

Natasha Chychasova is a curator and researcher from Donetsk, based in Kyiv. She works on strategies for the deconstruction of post-Soviet legacies, and feminist art practices. She is the Head of the Contemporary Art Department at Mystetskyi Arsenal, one of the largest cultural institutions in Ukraine. At the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, she curated the online platform Ukraine Ablaze, which aims to share information about Ukrainian artists and their works which, since 2014, have reflected on war. Her curatorial projects include: “This is not a Museum, this is a Plant” (Dnipro, Ukraine, 2020); Heart of Earth (Kyiv, Ukraine, 2022); “Forms of Presence” (2023); “Coexisting with Darkness” (Kyiv, Ukraine, 2023-2024); and “Between Farewell and Return” (Kyiv, Ukraine, 2024). She is also the co-author of Collective Fantasies and Eastern Resources alongside the artist Kateryna Aliinyk.

Published 6 March 2025

- Makov, Pavlo. «ДОНРОЗА. Щоденник українського розаря» [DONROSA. Diaries of a Ukrainian Rose Gardener], https://www.makov.com.ua/artbook/donrosa-art-book. [Translation by SONIAKH].

2. Maksym Vikhrov, «Дикий Схід. Нарис історії та сьогодення Донбасу» [Wild East. An Essay on the History and Present of Donbas], (Kyiv: Tempora, 2021), 52.

3. In reference to the mythical South American city of gold.

4. Volodymyr Kulikov, Iryna Sklokina, «Люди мономіст: парадокси єдності й поділів» [‘People of Monotowns: Paradoxes of Unity and Division’], in Праця, виснаження і успіх. Промислові мономіста Донбасу [Labor, Exhaustion, and Success: Company Towns of the Donbas], (Lviv: FOP Shumylovych, 2018), 118.

5. Oleksandr Teliuk, «Між ентузіазмом і катастрофою: образ Донбасу в українському радянському кіно» [Between Enthusiasm and Catastrophy: the Donbas image in Ukrainian-Soviet cinema], Historians, 2016, accessed February 25, 2025, https://www.historians.in.ua/index.php/en/doslidzhennya/1845-oleksandr-telyuk-mizh-entuziazmom-i-katastrofoiu-obraz-donbasu-v-ukrainskomu-radianskomu-kino

6. Borys Antonenko Davydovych, «Земля палає» [The Earth is on Fire], in Землею українською [Through the Ukrainian Land], (Krakow: Ukrainske vydavnytstvo, 1942), accessed February 25, 2025, https://diasporiana.org.ua/ukrainica/antonenko-davydovych-b-zemleyu-ukrayinskoyu/

7. Tetiana Portnova, «Ландшафти Донбасу» у Праця, виснаження і успіх. Промислові мономіста Донбасу [‘Landscapes of Donbas’ in Labor, Exhaustion, and Success: Company Towns of the Donbas], (Lviv: FOP Shumylovych, 2018).

8. You can see the work on the artist’s website: https://www.makov.com.ua/work/donrosa#1/0/0

9. Makov, “DONROSA”.

10. Personal correspondence with the artist.

11.

12. Kateryna Aliinyk and Oksana Briukhovetska, “Kateryna Aliinyk”, Secondary archive, 2023, https://secondaryarchive.org/artists/kateryna-aliinyk/

13. Howard LaFranchi, “In Pokrovsk, Ukraine, a rose is a rose – and a sign of resilience and hope”, The Christian Science Monitor, 2024, https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Europe/2024/0617/ukraine-war-donetsk-roses-hope

14. The official website of the rose nursery can be found here: http://www.rozesad.dn.ua/.