Translating Decolonial Glossary (and Myself) into Ukrainian Contexts

A writer and a researcher Viktoriia Grivina reflects on the process of adapting decolonial studies to Ukrainian realities and the challenges involved. Referring to her own experience in both Ukrainian and international academia, the researcher proposes a focus on a global collaboration in developing a shared vocabulary for Ukraine's ongoing cultural and intellectual discussion during the war.

At a recent presentation of Ukrainian Decolonial Glossary in Dnipro, a notable discussion occurred between the team of the Dmytro Yavornytskyi Museum on the one hand, and the Glossary team on the other. A museum’s representative wondered if it might be ethically problematic that an academic based in Berlin or, say, Lviv, would advise on museum transformations to practitioners who live near the frontline and have immediate experience of the challenges at hand. This criticism, coming from the embodied experience of a Dnipro local, has a valid point, and gives food for thought. Really, who should write Ukrainian decolonial theory? Can decolonial and post-colonial studies be cultivated within Ukrainian institutions with the same success that potatoes, corn, or sunflowers were once acclimated to local soils? How do we start a dialogue between the decolonial researchers of Ukraine and Ukrainian institutions when the researchers’ positionalities are dual at best?

Creating the first comprehensive assemblage of decolonial terms, the Ukrainian Decolonial Glossary team aimed to bring the concepts widely known in Western European and wider global academia onto local soil. The publication of the first 20 entries of the essential terms has largely been a success. On the same day the Glossary appeared online, a Ukrainian colleague of mine at St Andrews University thanked me for the link, saying that (after many months of nodding along to my speeches) he had ‘finally discovered what epistemic injustice was.’ I myself have been returning to the definitions of heterochronotopy and mnemonic war during my research on cultural narratives in Kharkiv. The changing perception of time during a traumatic event, as the war is, corresponded with a slow violence of memory and temporal distortion that the imperial culture imposes.

Returning to the Dnipro discussion, I could imagine myself, the product of Western academia, sitting there in front of the representatives of a local institution and looking like the proverbial Varangian who, as legend has it, came to Kyiv to rule over the Indigenous tribes, bringing the ‘light of civilisation’.

Surely, unlike Varangians, the authors of the Glossary are both Ukrainians and scholars of Ukraine. However, like me, many of them aren’t Ukrainian scholars. That is to say, they don’t belong to Ukrainian academic or cultural establishments. As such, we seem to be constantly suspended ‘in-between’: both international and Ukrainian; Ukrainian- and English-speaking; state-funded and sponsored by foreign grants (with unavoidable foreign interests or suspicions of such). Stuck in this institutional Surzhyk [1], as a member of the Ukrainian Glossary’s team, I can very well relate to the problematic nature of this position.

Trying to pin down my own positionality as a translator of the project, I want to start by looking at my personal background within Ukrainian and Western systems of knowledge. After a two-year Erasmus Mundus Master’s degree gained at three universities (in Germany, UK, and Italy) and funded by the European Commission, I am currently studying for a PhD in Scotland via a scholarship from the British government. By 2026 I will have spent more than six years affiliated with Western institutions, and over five living abroad. After that much time, truth be told, I’m often treated as a foreigner even by my own parents who jokingly call me ‘English girl’ (‘anglichanka’, mixing up the two British nations with unintended colonialism). I’ve spent all these soon-to-be six years researching Ukrainian culture. And yet, when asked about my right to study Ukraine while not being in it for such long periods, I have to muster the audacity to do so.

My case is very typical. Before going on a grand tour around Western universities, I graduated from V. N. Karazin Kharkiv National University with an MA in English and German linguistics. Coming back to that first experience, I can say that some of the courses in the philosophy of language, cultural studies, or theoretical linguistics in Kharkiv were more instructing than what I later learned in Western European universities and that I got the bulk of my knowledge from the rare and brilliant minds of some of our professors.

Like many of my ambitious colleagues, I even tried to pursue a PhD at home. But the enthusiasm faded soon when the spectre of the Soviet system emerged, with its unwritten rules, rites of passage, and humiliating gift-giving rituals that made me giddy. If I continue with this programme, I thought, I won’t respect this degree. Additionally, I was working at that time with predominantly English-language sources, and attending international conferences, which were frowned upon by local colleagues. Consequently, I never seemed to fit in. I felt like an involuntary translator between two systems, which led to exhaustion and a decision to never return to academia.

That ‘never’ lasted for just two years, after which I was offered two international scholarships – Erasmus Mundus (EU), and Chevening (UK). Having chosen the EU (in the end, Ukrainians are still such Euro-optimists), I embarked upon an Odyssey through European educational systems and was welcome to study Ukrainian culture from afar. The comfort that Western European universities provided came from the clearly regulated relations between me and the institution. All the rules were written on paper, and all duties, pre-agreed and official. The Soviet system was no longer hanging over me like a silent ghost.

Funding is always a painful subject for humanities, and having graduated during the pandemic I agreed to the first proposition that came my way—a one-year contract of an ‘early-career research assistant’, funded by a Scottish government grant. And here I was, employed by the Lviv Centre for Urban History, living in my hometown of Kharkiv, travelling between the Donetsk region, Kyiv and Lviv. Often when I approached a more traditional museum in the Donetsk region, the ethical conundrum would resurface, just like the one Dnipro discussion identified: who are you to talk to us?

My favourite story from that time is when a director of an archaeological museum in a town in the Donetsk region said to me, ‘We don’t need your help.’ Confused, I thought that maybe my affiliation in Lviv was the cause of suspicion. Trying to smooth things over, I reassured him that I was really from Kharkiv, to which the strict weathered director retorted, ‘Kharkiv, Lviv – all you Westerners are the same’ («Харків, Львів – ви западенці однакові»). Collaboration failed, even if I could now proudly call Kharkiv the much-desired ‘West’.

That said, it is through such – often difficult – communications that valuable resources of the Mariupol Museum, among others, were able to be digitised before the full-scale invasion. And so, when I was offered a position in the team of Ukrainian Decolonial Glossary, I could see that the potential benefits outweighed any ethical questions that we might face. I could for sure understand the tricky in-between position some of the project’s authors faced. Translating their articles together with my colleague Galyna Kotliuk, I had a unique opportunity to read the texts as they were still being amended, edited and even re-negotiated. Discussions regarding citing Russian translations of philosophical articles in the bibliography (ultimately we decided to replace them with the originals) and disagreements between the diaspora and local disguises regarding the correct Ukrainian spelling brought more and more questions revealing the particularities of Ukrainian decolonial language. Small notes on the margins could take weeks to negotiate. In his article ‘The Parergon’, Jacques Derrida argued that writings on the margins, footnotes and other remarks not only frame the main text but can change its meaning altogether [2]. Working on Decolonial Glossary was particularly interesting in those exact moments when such notes appeared. Because our backgrounds are so different, it helped us sometimes to go all the way back to the basic meanings.

In their famous work, What is Philosophy, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari [3] begin with a simple thought: that the most difficult thing in theory is to agree on the meaning of words, make sure that when we say something, the word we pronounce has the same meaning for every participant of the conversation. Clarification of meanings is important for successful communication between people and institutions, inside and outside Ukraine. It is a step to mutual understanding. Agreeing on definitions is also a way of resistance to the all-encompassing informational war that Russia is waging against Ukrainian and other democracies. With its enormous resources directed at media campaigns both inside their own state and abroad (the 2016 US elections come to mind) [4], Russia often manipulates the same language that Ukraine is using to refer to it, and which Decolonial Glossary explores — for example, imperialism, fascism, and neo-colonialism [5] — for its own propaganda purposes. Using abstract concepts such as war, peace, or “special military operations”, has been a powerful tool in the bag of dictatorial regimes across the globe. Establishing the exact meaning of words is thus both a very difficult task, and at the same time vital for the survival of Ukrainian culture, art, and academia. And even though positionality of the authors is important in the long run, the creation of shared terminology is urgent and therefore I believe should be done by all the interested parties. When a country is fighting a Just War, as David Rieff spoke about in his recent talk at the Kharkiv Literary Museum, which is to say defending from a clear aggression, with justice being on its side, then the best way to fight with the aggressor is to become a watchdog of truth, through being especially attentive to fact-checking, and the ethics surrounding obtaining and using information [6]. This kind of task set should be open to not only Ukrainian scholars, but all who honestly pursue shared language creation, and have the necessary expertise and the understanding of their own positionality. Decolonial theory toolkit is finely attuned to the trickiest cases of injustice, and therefore can be a suitable weapon for us as we face a very nuanced, complicated and powerful attempt at cultural genocide.

Finance plays a significant role in this uneven battle. A plethora of open letters by a variety of agents of influence, that call on Ukraine to subside to the Russian occupation, is an indirect result of Russian money that for years has been directed towards various institutions in the West [7]. The scarce number of Ukrainian Studies’ departments in the UK and EU is the result of lack of comparable financial interest. Many of the universities where I’ve had the privilege to study or attend conferences use ‘Russian’ as an umbrella term for all Slavonic or Eastern European departments Thus, research surrounding other areas of Eastern Europe goes unacknowledged, and effectively ends up contributing to the prestige of Russian Studies. Non-Russian scholarship in the field is therefore appropriated and concealed in the shade of Russian Studies. When universities change department names from ‘Russian Studies’ to ‘Post-Soviet-’, ‘Slavic/Slavonic-’ or ‘Eastern European-’ Studies, it often changes very little fundamentally, with the same Russo-centric curricula in place, while now formally providing degrees that would mark their graduates as experts in the entire regions or ethnic groups.

The existence until recently of the Russkyi Mir programme at St. Anthony’s College at Oxford University, directly funded by the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs [8], is but one case of the Russian state’s interest in staying in charge of the narrative within Western academia. In such circumstances the emergence of scholars who work on Ukraine internationally can be seen as an act of decolonial resistance. Thus, Ukrainians using all sorts of scholarships to bring Ukrainian research to the spotlight, is a solution to the constantly underfunded efforts of the Ukrainian state. Horizontal efforts of many individual enthusiasts, as it often is the case with our state-building, makes the difference.

And here, I have my own piece of advice for the Ukrainian Decolonial Glossary. More and more non-Ukrainian scholars are willing to dedicate their lives to the studies of Ukrainian culture, history and society (despite less generous financial opportunities that have only slightly improved post-2022). Thus, allies could be found among those who might have similar dual positionalities. The participation of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak at a recent Lviv Media Forum is a powerful sign of solidarity, with Spivak both representing Western academia and spending a lifetime on its constructive critique [9]. Furthering such solidarity might consolidate the community of Ukrainian Studies. Even on an editorial level, our short but intensive cooperation with Clemens Poole, an American artist and curator who was the English literary editor on the project, helped to broaden our perspective on how a person with a lived experience abroad could perceive the Glossary’s explanations. Creating an international community that would be working on writing and reading Decolonial Glossary together would provide a necessary field of solidarity and help international scholars advocate for our case in decolonial studies.

In the Ukrainian context, this new set of definitions should combine post- and de-colonial theories, ecofeminism and other studies (including such unlikely bedfellows as Saїd and Haraway, or Mignolo) to reflect the particularities of Ukrainian cultural space. If we want to be recognized as and seen through the lens of decolonial theory, the inclusion of non-Ukrainian scholars, artists, readers and cultural activists should be welcomed.

Surely, there are factions of international scholars who switch into Ukrainian studies for the reasons of dwindling financing of the Russian studies, and who would not be interested in the deeper knowledge of Ukraine, its language and history. However, it does not mean that we should do everything on our own. As Victoria Donovan notes in the article dedicated to academic resourcification, it is important to understand the ethical positionality of the scholar, and such positionality might not necessarily depend on the person’s ethnic, economic or socio- cultural background, but lean on the willingness to understand the local context, travel to Ukraine, and to learn the language and history of the country [10]. Knowledge production regarding Ukraine is an important step for creating a critical mass of scholarship that will help form a strong footing for Ukrainian Studies in future. With the critical and systemic problems of Ukrainian academia when it comes to funding, it would be unwise to discard help and possibilities of collaboration between scholars and the institutions that support Ukraine-focussed scholarship worldwide.

On a personal note, I would say that although the criticism of foreign affiliations of Decolonial Glossary and many of its authors, heard at the discussion with the Dnipro museum’s employees, is valid, our decision to work for and study at foreign institutions is often a survival strategy.

I don’t have a place in Ukrainian academia today. Coming from a family of modest income, I see the reasons as not only ideological, but economic too. A child of the 1990s, I live in constant fear of dying of hunger. I take every opportunity that corresponds to my ethics. Furthermore, Ukrainian institutions have been hit hard by the war. In Kharkiv this is the case both physically and financially. For a variety of reasons, including lack of socialisation, students chose safer environments in the west of Ukraine or abroad. An indirect proof of the crisis of higher education in the Ukrainian east can be seen in the repeated attempts by the Ministry of Education to merge various institutions with V.N. Karazin National University [11]. Recent Kharkiv’s PhD graduates I’ve spoken with are made to seek teaching opportunities across the country, faced with the staff cuts.

In contrast, international support for Ukrainian academia has never been stronger. The British program of coupling universities in the UK with Ukrainian ones and providing generous grants for cooperation is one example [12]. Having some knowledge of English and being familiar with academic applications can open a wide and generous path for an apt Ukrainian academic. Sometimes, as in the case of male scholars, institutions even agree to online cooperation and non-residence grants., where a researcher can stay in Ukraine, but with international affiliation better research funding. Here, ethical aspects come to the fore. Who sponsors a programme, are these people affiliated with Russian institutions or grant-givers, and so on.

In this ethical aspect, Decolonial Glossary has, in fact, highlighted a phenomenon which I hadn’t thought about myself — that of the Ukrainian diaspora. For decades prior to Ukrainian independence, the descendants of people who fled Ukraine, had been putting effort in preserving Ukrainian culture in the form that wasn’t impacted by Soviet and Russian imperial policies. One of the curators of the project, Myroslav Shkandrij, a Canadian-born Ukrainian, uses his non-Soviet perspective in his sharp analysis of colonial processes and painful subjects of our history. Similarly, Gennadi Poberezny, the author of the Glossary article, Raphaël Lemkin’s Concept of Soviet Genocide in Ukraine, uses his diasporian background to conduct a very precise dissection of this complex topic. In the Ukrainian version of the article, Poberezny added two remarks. In the first one he insists on using ‘sovietske’ (‘совєтське’), a colloquialism for ‘Soviet(ness)’ assimilated to Ukrainian from Russian (as opposed to ‘radianske’ (‘радянське’) – the literary Ukrainian translation of ‘Soviet’) with the intention to denote this regime as foreign for Ukraine. In the second remark, Poberezny explains using the 1928 ‘Kharkiv Spelling’ as a practice of ‘de-Sovietization’ of contemporary Ukrainian orthography. Such attention to the details that were part of the colonisation of Ukrainian culture, is something that I could not easily see, even being a Kharkiv native. I was born and educated using the Ukrainian spellings of the 1990s which weren’t that different from Soviet ones. Even so, I remember my older brother going berserk when the apostrophe was introduced back into the alphabet. For him, the spellings he had been taught were something eternal and no amount of explanations could change his opinion. As today the orthography slowly approaches the standards of the aforementioned ‘Kharkiv Spelling’, we can see how complicated the process is. This puts the diasporic author in a uniquely privileged position to identify such fundamental details.

With all of these haphazard thoughts in mind, my current answer to the question of who has the right to create Ukrainian Decolonial Glossary would be unoriginal. It should be a communal effort, I’m sure. A case of hard, sometimes conflicted collaboration between Ukrainian scholars and activists, scholars of Ukrainian heritage, and scholars of Ukraine who share a feeling of moral responsibility to help those fighting for freedom. The team of Ukrainian Decolonial Glossary have mustered the courage to take the first step, and to my mind, they are moving in the right direction. The talk with the museum workers is in itself a good sign that such understanding exists, that the need to reach out across the institutions has been identified as important. And though I myself love staying in my comfortable cultural bubble, I too understand that decolonisation requires getting out of it. And so, Decolonial Glossary needs to continue reaching out, beyond mutual comfort zones to create a truly universal language of Ukrainian decolonial studies. I wish them all the success.

Ukrainian Decolonial Glossary is supported by the European Union under the House of Europe programme.

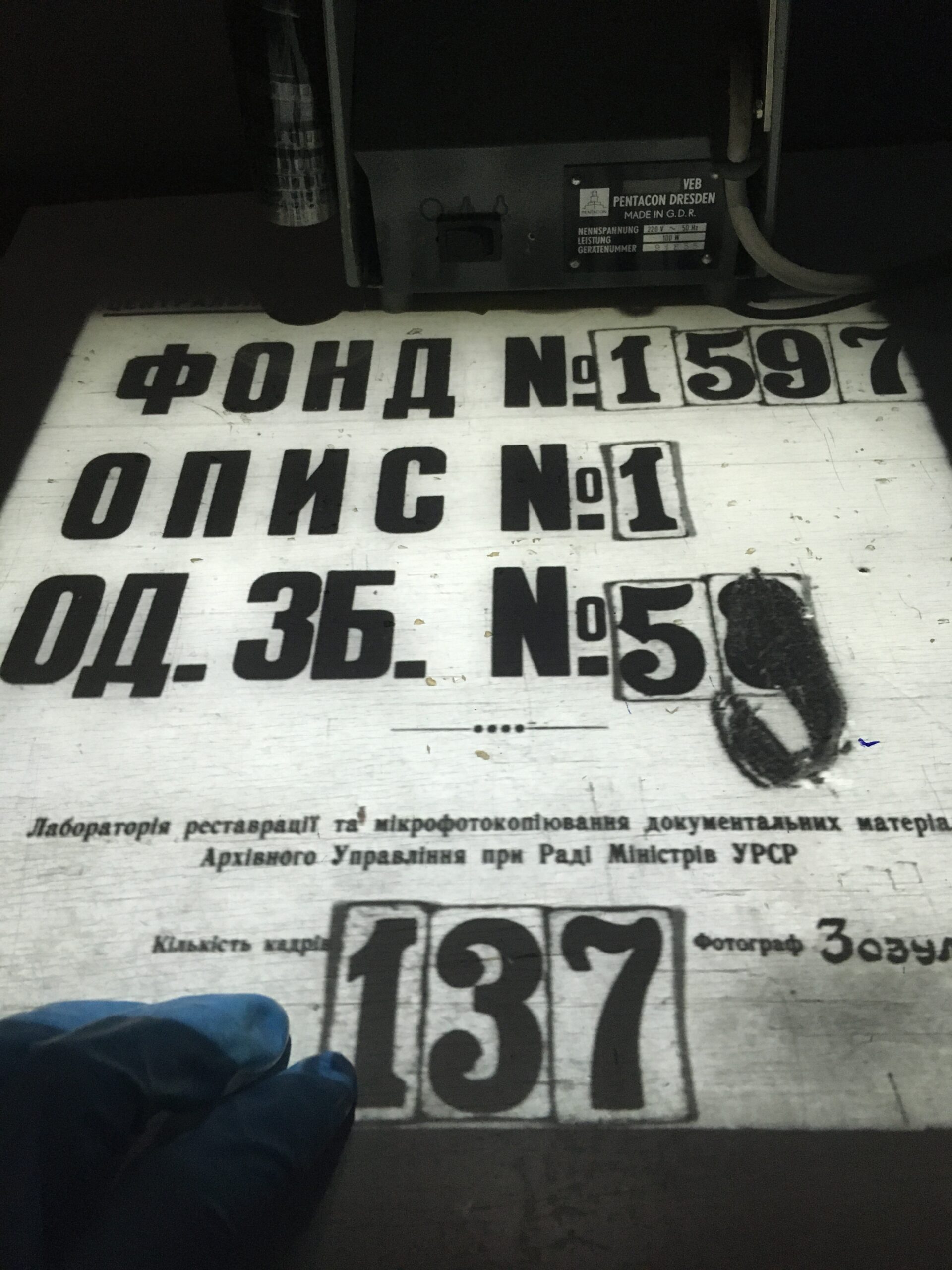

All the pictures are taken by Viktoriia Grivina during her work in Donetsk region.

Editing by Ada Wordsworth.

Viktoriia Grivina is a writer and cultural researcher from Kharkiv, Ukraine. She holds a Master’s degree in linguistics of Kharkiv National University, and MA in Cultural Studies via Erasmus Mundus Master’s Scholarship (at Tübingen, Bergamo and St Andrews universities). In 2020-21 she was an early career researcher at ‘(Un)Archiving (Post)Industry’ Project, digitising photographic legacy of Donbas, Ukraine. Her current PhD research at the University of St Andrews is dedicated to the transformation of cultural and aesthetic landscapes of Ukrainian cities in times of war.

- Surzhyk is a socio-linguistic phenomenon particular to the Ukrainian linguistic space that combines the assimilated elements of both Ukrainian and Russian languages. Its history is connected both to organic development and contact of two languages and the history of Russian imperialism and language prohibition politics.

2. Jacques Derrida and Craig Owens, “The Parergon,” October 9, no. 166 (1979), 3–41. https://doi.org/10.2307/778319.

3. I first read this book at Kharkiv National University – and felt it important to state to undermine the hierarchy of my own educations, Western vs Ukrainian, where every university had its own strengths and weaknesses irrespective of where they were located.

4. Andrew R. N. Ross, Cristian Vaccari, and Andrew Chadwick, “Russian Meddling in U.S. Elections: How News of Disinformation’s Impact Can Affect Trust in Electoral Outcomes and Satisfaction with Democracy,” Mass Communication and Society 25, no. 6 (2022). 786–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2022.2119871.

5. “Putin proclaims end of ‘ugly neo-colonialism’”, France 24, accessed June 2023, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20230616-putin-proclaims-end-of-ugly-neo-colonialism.

6. The information about the event: https://www.instagram.com/p/C83xiNrtF__/.

7. “The Nato alliance should not invite Ukraine to become a member”, The Guardian, accessed July 2024, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/jul/08/nato-alliance-ukraine-member.

8. Russkyi Mir in Oxford, Facebook, accessed August 2024, https://www.facebook.com/groups/417889414915901/; “Russian Translation Workshop”, (an event in the Russkiy Mir Programme at St Antony’s College. It is supported by CEELBAS, the Russkiy Mir Foundation, and the Mikhail Prokhorov Foundation), accessed August 2024, https://www.scoop.it/topic/translation-world/p/4001498772/2013/05/12/russian-translation-workshop-school-of-interdisciplinary-area-studies.

9. The details of the event could be found via the link: https://lvivmediaforum.com/en/page/oleksandra-matviichuk-and-gayatri-chakravorty-spivak-will-become-the-keynote-speakers-at-x-lmf.

10. Victoria Donovan, “Against Academic ‘Resourcification’: Collaboration as Delinking from Extractivist ‘Area Studies’ Paradigms,” Canadian Slavonic Papers 65, no. 2 (2023), 163–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/00085006.2023.2200669.

11. An attempt to merge Kharkiv’s pedagogic university with Karazin has caused a particular turmoil and a wave of protests from both the Pedagogic university staff and wider academic community with the hashtag #SaveSkovorodaUniversity: https://kharkiv-nuau.hneu.edu.ua/2024/01/06/saveskovorodauniversity/.

12. Twinning Initiative, https://www.twinningukraine.com/.

13. The Ukrainian orthography of 1928 was further banned as ‘nationalist’ by the People’s Commissar for Education of the UkrSSR in 1933 and replaced with the new Ukrainian orthography of 1933 that brought Ukrainian spelling closer to Russian rules. It continued to be used with minor changes thereon including the times after the break of the USSR until the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine approved a new Ukrainian orthography of 2019 that brought back some features of the 1928 standard.