On Being Emotional Infrastructure

‘No one felt emotions before about 1830. Instead, they felt other things — “passions”, “accidents of the soul”, “moral sentiments"’ [1]. We made a huge leap from the fog of emotional life and found ourselves as emotional ‘data subjects whose rights and existence are conditional upon their behaviour within digital networks’ [2]. What 200 years ago was considered something obscenely irrational has been successfully turned into an asset – the developers of digital platforms have studied emotional states enough to commodify them. In military campaigns, such as the Russian invasion of Ukraine (before 2022 and after), commercial emotion-generating techniques have been developed to the extent of becoming a form of exhausting emotional extractivism.

The text sews together academic views, premonitions and subjective interpretations, technical and legal data, and art sketches in order to reveal the mechanism of transforming emotions into infrastructures for cyberwar propagation. This is also an attempt to map Russia’s tactics and techniques involving the occupation of ordinary citizens' imaginations to reinforce its controls in areas that it cannot destroy, erase, or capture physically.

Internet

Viacheslav Husakov, a journalist from Kherson’s regional media outlet Most (Bridge), continued to work in Kherson during its occupation by the Russian Armed Forces. He recalls quite a few shutdowns, occurrences which had specific relevance to him due to his professional reliance on communication infrastructures. In particular, he remembers the shutting down of mobile network carriers, local and country-wide internet providers in Ukraine, and power supply companies. He says that printed media stopped coming into Kherson in February 2022, when the fighting in the region began, even before the occupation of the city. Ukrainian television networks operated until April, and the Ukrainian FM radio was broadcast on-and-off throughout the city’s occupation. In March 2023 the Russians ‘took control’ of Ukraine’s global internet provider Kyivstar whose internet was available till April.

‘The cutoffs of communications and internet started in early April, ranging from several hours to 2-3 days. Most probably, this was due to “jammers”, possibly connected with the movements of the occupiers’ military machinery. The shutdowns did not last long but this caused certain issues in my work. The most serious internet issues began in late April. At that time, local internet providers were forced to re-route traffic to the Russian provider Miranda-Media.’ [3]

Miranda-Media is a Crimea-based Internet provider founded by Russians in 2004. As of May 2024, 80% of the entity is owned by Luxtrans Shipping Company, and another 20% — by Russia’s state-owned Rostelecom. The latter were registered as owners on 19 February 2014, one day before Crimea’s annexation, with control of 100% of the shares. Luxtrans became the co-owner of Miranda-Media only in 2015. Overall Miranda fulfilled 985 state orders for the Russian government, most of them in the Crimea. This included commissions by military units, the Pogranichnik Clinic and Sanatorium (a clinic run by the Federal Security Service of Russia), and the Crimean Prosecutor’s Office, as well as by hospitals, railroad authorities, and other strategic facilities.

Switching Ukrainian providers to Miranda’s traffic meant that Ukrainian users would only have access to Russian resources. The Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media (abbreviated as Roskomnadzor) blocks oppositional Russian resources, Ukrainian media, and foreign resources which are perceived to ‘constitute a threat’, such as Facebook and Instagram. As of May 2024, a total of over 1.7 million websites have been blocked in the Russian Federation according to an unofficial register.

On 4 May 2022, the owner of Kherson’s major internet provider, Kherson Telecom (Skynet), Dmytro Hudz published a post on Skynet’s Facebook page, stating that he had been forced to switch to Miranda’s traffic as there was no other option for providing internet access to the citizens since the usual (Ukrainian) routing no longer provided any traffic.

He wrote: ‘On 1 May I was forced to turn on the channel of the Crimean operator Miranda. In just one day, between 2-3 May, my company experienced an unexpected shock… People began to queue in huge numbers around our offices to use the network. […] On 1 May Oblenergo employees [employees of the regional electricity supplier — author’s note] bid online for electric power from my office so that the region would not lose electricity. They simply did not have any other means of communication!

On 13 May, the State Special Communications Service of Ukraine released a statement that ‘terrorists from the so-called national guard of the russian federation [sic] have seized the premises of Status, a Kherson-based company, [another Internet provider — author’s note] and disconnected all communications equipment […], they are threatening the company management with the seizure of all the equipment if the management refuses to connect to the Crimean network.’

Later on, Status’ owner gave a statement to the Ukrainian resource dev.ua, in which he said the same thing as Dmytro Hudz: that connecting to the Crimean network was the only way of providing internet to Kherson. According to a dev.ua post in September 2022, Status was directly connected to Miranda. Two more local providers, Pluton and Ukrkom, were receiving traffic through Status.

‘They said that this way they would supposedly be able to both offer high-quality internet and increase control over the local population simultaneously,’ says Viacheslav. ‘It was reported at the time that Russian IT geniuses had implemented some kind of tweaks to the network, thus ensuring that not a single person supporting Ukraine would be able to hide. But I think that was bravado. Occupation has several inevitable features: the first thing necessary is to make people scared, to occupy psychologically. I think that was the intention. But one thing to note is that all VPN services were functional at the beginning of the full-scale invasion, even the free ones, and then Russians blocked them, making it harder and harder to use them.’

Mobile Connection

Generally, the mobile connection disappeared in Kherson on 30 April 2022. But ‘islands of communication’, as Viacheslav calls them, remained till early July. One network mast, operated by Lifecell, a Ukrainian branch of a worldwide mobile network operator, was situated near to the Dniprovska District Council building.

‘A lot of people would gather there. We would go there to call relatives. People who were paid retirement benefits at Oschadbank [Ukrainian state bank — author’s note] went there because they needed to receive a message on their mobile phone, that’s the procedure for getting the money. But the Russians disconnected the tower in early September and dispersed the crowds.’ says Viacheslav.

In May 2022, the occupiers started selling +7Telecom mobile operator’s cards. The SIM cards did not have any markings, nor did the operator’s website feature information about any legal entity carrying out commercial activities. According to the web archive, for the first time, the name of the legal entity K-Telecom LLC responsible for the work of the mobile operator appeared on the website only in March 2024. At the same time, the 7telecom.ru domain is registered in June 2022 in the name of a Russian entity, JSC IC8 (Aysi Eyt LLC) founded in May 2021 in Gelendzhik, a city in the Russian Federation. IC8 belongs to IC Invest which also manages two Crimean mobile network operators — KTK Telecom and K-Telecom. All the above entities are owned by Pavel Kuznetsov, a former manager of the Moscow companies Intellect-Telecom (which specialises in telecommunications) and Sitronics (which specialises in IT). Both projects had previously collaborated with the Russian government.

During a Crimean conference arranged for the employees of IC8, KTK Telecom, and K Telecom in September 2022, Kuznetsov himself stated that: ‘This is not an easy time but the challenges it brings stimulate all the hidden potential of Russian IT specialists and managers, making them totally reconsider their approaches towards the creation of new products. Now is the time to work quickly, precisely, and consistently.’

Each person in Kherson was able to buy no more than five +7Telecom cards, and had to present their passport for every purchase, so as to allow personal espionage by the occupation authorities. Viacheslav spoke about the countermeasures used by Kherson citizens: ‘The occupiers did not take into account the inventiveness of Ukrainians! People bought the cards using their passports and resold them, so as to undermine the Russian attempts at personal espionage. I bought a card this way. I overpaid for it, but in the end it was the option to have communication at a certain point in time. Some people also purchased the cards before giving them away to Kherson volunteers for whom it would have been dangerous to reveal their data.’

Russians even started a special campaign to counter unauthorised card resales: they warned against buying cards from individuals, raided locations, prosecuted second hand sellers, and made false claims that the cards were non-functional.

The mobile internet offered by +7Telecom was slow, expensive, and unavailable in several areas of the city, but from September 2022, it became the only means of communication.

‘As a result of the limitations placed on communication networks, I noticed an informational vacuum emerging, which subsequently led to people becoming increasingly reliant on Russian sources. Somewhere around the summer ordinary Kherson residents began to sometimes adopt Russian propaganda narratives in their conversations: “Ukraine has forgotten about us, and we need to live on, maybe we will live somehow with “those.” Whilst this was only a small portion of the population, it nonetheless indicates that for some people, the vacuum was truly filled by Russian propaganda’, Viacheslav said.

On 6 November all forms of communication networks, electricity, and water supply disappeared in Kherson. This was the Russian preparation for their so-called ‘gesture of goodwill’—the retreat from Kherson.

Vacuum

Tavriisk is the centre of an eponymous hromada (municipality) in the Kherson region, located on the left bank of the Dnipro River, about 80 kilometres from Kherson. The town was occupied on 24th February 2022, the first day of the full-scale invasion by Russia. According to Svitlana, the director of a local school, during the first days of occupation, the Russian troops were not stationed in the town itself, instead being based five kilometres away in the neighbouring town of Kakhovka. They controlled all entrances and exits to both cities. Just like in Kherson, mobile internet here would disappear sporadically throughout the occupation, and was dramatically slower than usual when it did appear. Since June 2022, uncensored internet has been available through the use of a VPN.

‘The Russians checked passports at security checkpoints, and phones too, looking for pro-Ukrainian photos or comments. Only men were checked at first but later they began entering buses and checking everyone — sometimes passports, sometimes phones. And if, for instance, you were subscribed to a Ukrainian Telegram channel, you could end up “in the basement” [in a torture room which Russians often set up in basements — author’s note]. So each time you pass this checkpoint, you need to delete everything and completely clear your history and cache. I would not say we were heavily pressured, but this uncertainty affected us because we did not know where to look for the truth. This informational vacuum was frightening, and in a way was probably the worst part of the occupation, and it is hard to explain. Despair and fear.’

Svitlana left the town on 30 June 2022. Having made the decision very quickly, she considers herself lucky, both to have been able to leave the Russian-occupied territories and to have reached Ukrainian-controlled territory quickly, with the whole journey taking under 24 hours. Having left, she continued working remotely as the director of Tavriisk School, which incorporated the schools of seven villages of Tavriisk hromada. Classes were offered to everyone who is able to access the internet. As of October 2024, there are 640 pupils, 266 of whom are in the temporarily occupied territories.

‘People went out of their way to find ways of coping. If Wi-Fi was available in a neighbouring house, then people would gather outside it, trying to connect. With increasing prices and high levels of unemployment, groups of neighbours would club together to pay for a one-month package.

Likewise, children would wander around the streets in search of a connection. They could not connect to Google Classes because the Russian military often visited the parents of our students and conducted searches, checking phones, tablets, and computers for evidence of Ukrainian language learning. If you were found to have partaken in Ukrainian classes, you would be beaten. Upon finding a signal on the street, children would download assignments, completing them at their own risk, and then sending them away for checking.

It is the same story with the news. Russian media narratives were obsessed with “Ukrainian Nazis” and “Ukrainian fascists”. They would shell us and claim the shelling had been committed by Ukrainians. Those who owned satellite televisions could watch Ukrainian channels. In the evenings, they would gather with their neighbours and share the truth of what was going on.’ says Svitlana.

All subsequent Russian actions surrounding communication in the Russian-occupied territories since our interview with Svitlana have only contributed to the further construction of a ‘vacuum’ or a kind of hybridised echo chamber – partly offline, partly online.

On 13 May 2023, Miranda Media announced its plans to become the only telecommunications service provider in the so-called ‘DNR’ and ‘LNR’, as well as in the occupied areas of Zaporizhzhia and Kherson regions. As of September 2024, traffic has been exchanged between the Russian Miranda and twelve Ukrainian providers.

In July 2024, Novoe.Media, a media platform specially created for the ‘new regions of the Russian Federation’, reported that there were two more cellular operators currently operating in the Kherson region except the already mentioned +7Telecom: Phoenix and Mirtelecom. A separate Mirtelecom domain is not operational and is registered at RU-CENTER-RU, the Russian government registry. The same registrant has the rights to the Phoenix domain, thus maintaining the limited selection of choices of operators in Russian-occupied territories.

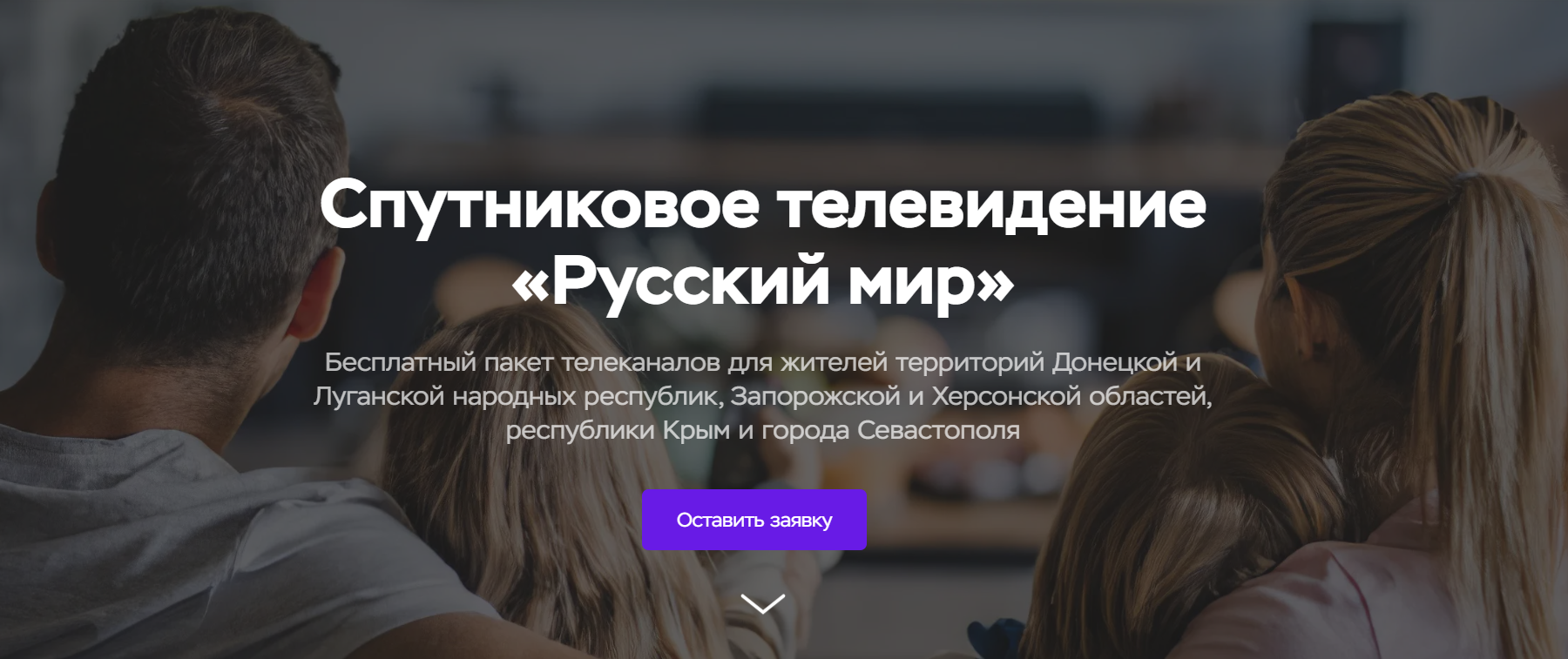

This is only the beginning of Russia’s plans for ‘vacuumisation’. For instance, the ‘Russian World’ satellite television channel, which started operating in autumn 2022, specifically for the Ukrainian temporarily occupied territories, guarantees its subscribers on occupied territories ‘free viewing of all programmes until 31 December 2026’.

Distort, Dismay, Divide

A Russian soldier who randomly checks passports or smartphones at a checkpoint in the Russian-occupied territories is the best example of contemporary occupation procedures. Your passport, of course, says a lot about you, but your smartphone, which stores data on all your subscriptions and preferences, contains much more meaningful information. The only way that a Russian soldier could more effectively vet citizens by checking their Google ad cabinets.

Well-researched data [4] surrounding emotions yields massive commercial benefits for digital platforms. For an extra fee, it can help to create targeted commercial and political advertisements, using the logic of emotional extractivism. Based on this logic, digital platform users must always be excited and stirred up (angered, happy, exalted) in order to ‘share emotions.’

The notion of ‘communicative militarism’ proposed by Svitlana Matviyenko provides a comprehensive description of how digital infrastructures, using all those aligned mechanisms of provocation, are appropriated by states in the interests of cyberwar. [5]

Another Ukrainian researcher Lesia Kulchynska in the text Violence is an Image: Weaponization of the Visuality During the War in Ukraine, describes how the very act of spreading images of atrocities committed by the Russian army in Ukraine is transformed into new weapons against the Ukrainian population.

‘To transform the images of atrocities conducted by the Russian army into weapons certain infrastructure is needed as well. Which is an infrastructure of fear, or to put it more precisely, the infrastructure of power and social relations based on fear. That is an infrastructure of authoritarian rule based on the force that is operative, particularly, in contemporary Russia.’ [6]

Lesia Kulchynska goes on to talk about the feelings of guilt. This is a state experienced by a huge number of Ukrainians, in particular when photos featuring people killed and tortured in the territories occupied by Russia are spread. She analyses the use of this guilt to be an additional suppressive tactic against Ukrainians, revealing the weaponization of this emotion.

Military-industrial complexes are able to avoid spending their budgets on the machines of visualisations of our personalities – that is to say, our emotions, thoughts, feeling structures – instead only needing to pay for operators. This is because everything has been created in advance – for commercial purposes by digital platforms. However, the weaponization of users’ emotions has now reached such proportions that states are forced to provide additional budgets to counter such influence campaigns. Such military emotional campaigns are also known as FIMI – ‘Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference’.

As defined by the European External Action Service, it is ‘a pattern of behaviour that threatens or has the potential to negatively impact values, procedures, and political processes. Such activity is manipulative in character, and conducted in an intentional and coordinated manner. Actors of such activity can be state or non-state actors, including their proxies inside and outside of their own territory.’

Distort, Dismay, Divide. These are just three of more than 150 separation techniques that have been categorised and described by the US-based NGO DISARM to counter such information threats. These days their framework for counteracting is an industry standard in the US and the EU. The framework also involves response techniques, including ‘repair[ing] broken social connections’ or ‘reduc[ing] the effect of division-enablers’.

Thus, you can imagine the Russian imperial machine as a giant purchase funnel. This marketing technique is called a funnel because it allows you to weed out those who are not ready to make a purchase by constantly narrowing it down while targeting those who are. Let’s say, in such a funnel, at the entrance, hundreds of specialists use FIMI to select offers that may be of interest to a group of people like you. And its final purchase – is the physical occupation of your home territory.

Unfortunately, the aforementioned tactics of countering FIMI are not appropriate in the context of occupation. FIMI is a method of emotional occupation, the maintenance of which makes physical occupation possible. It is only after FIMI that all of the development of a hybrid infrastructure, where our emotions play a final decisive role – if the army of occupiers cannot destroy, erase, or capture physically.

Emotions as Infrastructures and Imagination as Technology

Emotions are ever-present in discussions surrounding communication infrastructures, but generally not in the role of the components of the infrastructures. In his article, “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure” Bryan Larkin also gravitates toward this vision. ‘Infrastructures are metapragmatic objects, signs of themselves deployed in particular circulatory regimes to establish sets of effects’, he writes. Still, he leaves space for interpretation in this text (namely for machine ensembles and digital infrastructures) — a space which we intend to fill.

In this text, Larkin quotes researcher Thomas Hughes as saying‘[…] Infrastructures typically begin as a series of small, independent technologies with widely varying technical standards. They become infrastructures when either one technological system comes to dominate over others or when independent systems converge into a network.’ The same thing is happening in Russian-occupied territories: influenced by a combination of physical intimidation, militarised social media marketing and Soviet-era TV propaganda, gaslighting, paranoia, and digital platforms’ (meta)data – emotional states are dehumanised and forcefully appropriated for subsequent integration into the existing system of influence. So, if our emotions are already mapped, doesn’t that make them a ‘technology with widely varying technical standards’?

Recognising that our emotions can be appropriated and become infrastructures spreading cyberwar does not mean refusing agency. On the contrary, this is a way to reinforce it. The issue of human emotions and decisions taken under their influence is not just a ‘human factor’ to which all uncertainty is traditionally attributed. This is a calculated elaborate tactic used by the occupiers. People finding themselves under the influence of informational military tactics should not be stigmatised. These are people who need more information about terrorist tactics, techniques, and procedures.

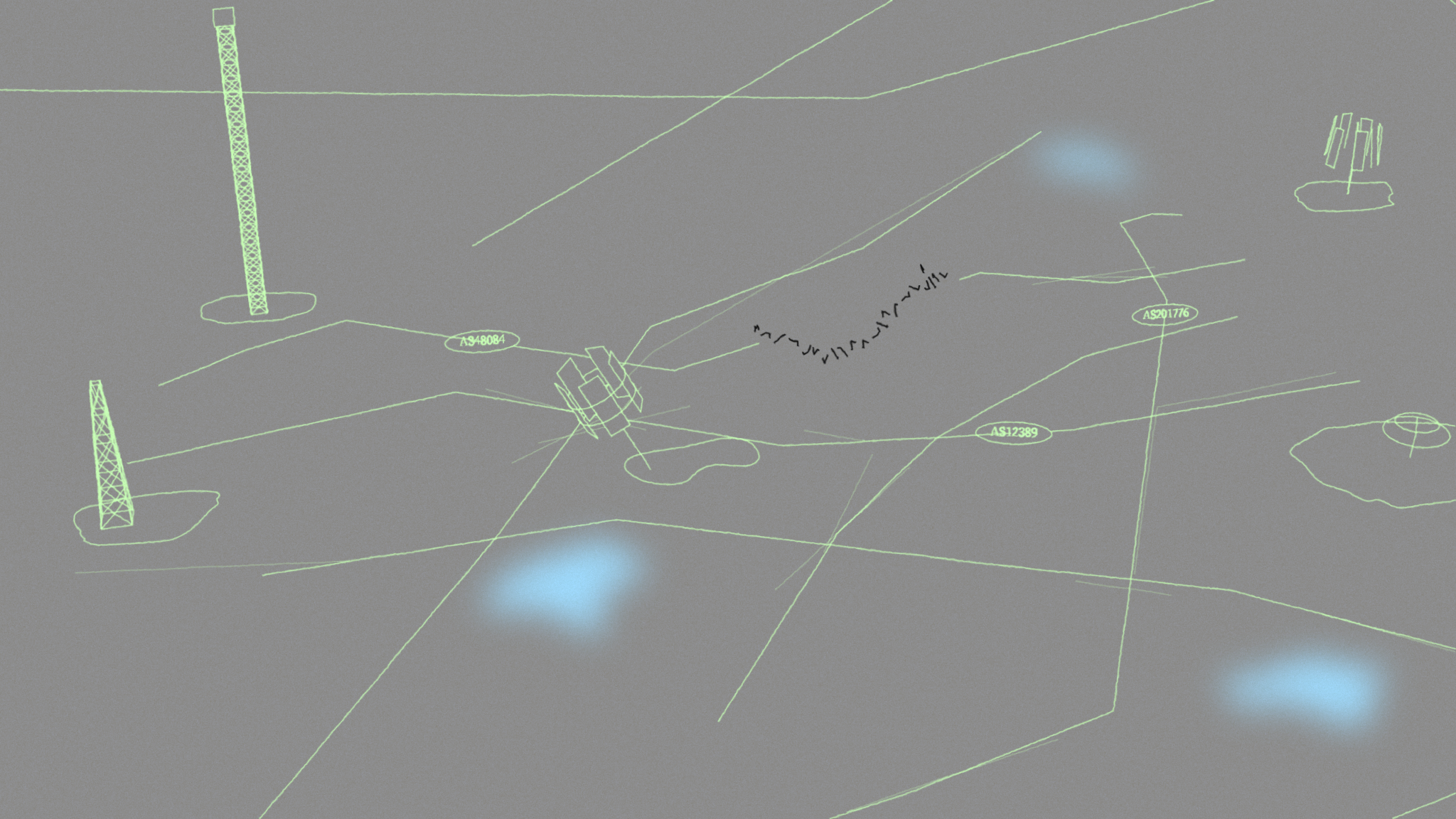

By recognising that our emotions can be used against us, we can embrace the ability to build effective, shimmering human networks *˚which may disappear here and reappear there*• so as to create our own mixed infrastructures. We can see these networks in the neighbours who shared news from non-Russian satellite channels, or the protection of volunteers in Kherson through the anonymisation of SIM cards, or the collective purchase of a single internet package for several apartments. It is through the erection of such fragile networks that we can liberate the space of our imagination from occupation by the imperial fantasy.

The text was started during the residency ‘Bodies as Lands — Sociotechnical Imaginaries and Spatial Arrangements in Eastern Europe’ held in March 2023 at Nida Art Colony of the Vilnius Academy of Arts and was completed during 2024 in different places in Ukraine and outside.

Editing by Ada Wordsworth.

‘fantastic little splash’ is a collective comprised of journalist/artist Lera Malchenko and artist/director Oleksandr Hants. “fantastic little splash” combines art practice and media studies to research collective imagination and emotions appropriation in technosocial systems. Group works with videos, texts and interactive game-based tools. Established in 2016 in Ukraine, their projects have been exhibited at events including transmediale, post.MoMA, Plokta TV, Ars Electronica, Liste Art Fair Basel, Construction festival VI x CYNETART, KISFF, and Docudays, among others. fantastic little splash – participants of the transmediale x Pro Helvetia Residency 2022, and the Cité internationale des arts residency 2023.

Published 15 October 2024.

- Tiffany Watt Smith, The Book of Human Emotions, (London: Profile Books, 2015).

2. Svitlana Matviyenko and Jaime Lee Kirtz, “Echo Chambers of Paranoid Knowledge: On Cyberwar Epistemology,” Discourse: Journal for Theoretical Studies in Media and Culture, Vol. 45: Iss. 3, Article 6 (2023): https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/discourse/vol45/iss3/6.

3. All comments by Viacheslav Husakov, a journalist from the Kherson media outlet Most, and Svitlana, a director of a school in Tariisk, were made in interviews with fantastic little splash.

4. Adam D. I. Kramer, Jamie E. Guillory, and Jeffrey T. Hancock, “Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Vol.111(24) (2014): https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4066473/.

5. Svitlana Matviyenko, “Cyberwar and Communicative Militarism,” filmed July 2021, GEPD UFRN, 1:13:23. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gRu2ic5FVjs.

6. “Violence is an Image: Weaponization of the Visuality During the War in Ukraine,” Lesia Kulchynska, accessed October 2022: https://networkcultures.org/tactical-media-room/2022/10/26/violence-is-an-image-weaponization-of-the-visuality-during-the-war-in-ukraine-2/.