Erased from Walls but Not from Memory

Since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Wall Evidence has been collecting and publishing photos of graffiti left on the walls by Russian soldiers in the deoccupied territories. SONIAKH's co-curator Valeriia Buradzhyieva spoke to the leaders of the initiative, Anastasia Olexii, Mariami Gubianuri and Roksolana Makar about the importance and challenges of archiving war crimes, the cultural roots of the genocidal vandalism and ways in which this testimony can serve as a tool in telling the world about the violence committed. If you wish to become a researcher for Wall Evidence, please contact the project at info@mizhvukhamy.com, if you have materials to add to the archive, you can fill out this form.

Valeriia Buradzhyieva: How was the archive created?

Anastasiia Olexii: In May 2022, Pavlo Haidai, the founder of the cultural institution Mizhvukhamy (editor’s note: through whose organisation the archive works), visited the liberated Hostomel with the philosopher Oleksandr Filonenko. During the occupation, Kadyrovite soldiers [1] lived in a school there, and left a collection of graffiti on the walls that interested Oleksandr. He wanted to study and categorise the messages, and so the first task was to collate and document them. We personally photographed some of the graffiti, whilst I found other instances of it online – with the recent liberation of the Kyiv and Chernihiv regions came the publication of many reports which included in them evidence of this graffiti.

Initially we recorded all the graffiti, including those of the local population and the Ukrainian military, but then we decided to limit ourselves to that which had been left by the Russian military to make this clear distinction. Judging by the material, the Ukrainian military did not engage in vandalism — they could, for example, write something on Russian military equipment that was destroyed, or add something to the preexisting graffiti done by the Russians. A recurring slogan found in the Kyiv region addressed to the Russians was ‘Welcome to Hell’. Sometimes Ukrainian soldiers were leaving the graffiti for practical reasons, for example references to mines. Nowadays we generally get sent photos of the graffiti by people who have found them in their homes following liberation, or by the military themselves. I then collect the images in a spreadsheet, describe the contents, and transcribe them. By July 2022 I had collected around 200 pieces of graffiti, and I began to think about what I could do with them, and what format I could use to showcase them.

I also wanted to interrogate why I was doing this, as at that point I was doing the project alone, almost without funding, because our funding had come from Mizvukhamy, however its funding came from the founder’s company, and the war caused this support to be ended. Later, with the support of the ‘Documenting Ukraine’ program of the Institute for Humanitarian Studies in Vienna, we transformed the collected materials into an open archive accessible to people dealing with the topic of war – artists, directors, researchers, etc. The main goal was preservation, because the graffiti appeared chaotically in the flow of information and its existence got lost in it. This was especially true in the first year of the full-scale invasion: due to the colossal avalanche of information, what was relevant in the morning had already lost its relevance by the afternoon. In ten years, people will know that these artefacts are documented and can be worked with.

Valeriia Buradzhyieva: Who is your target audience?

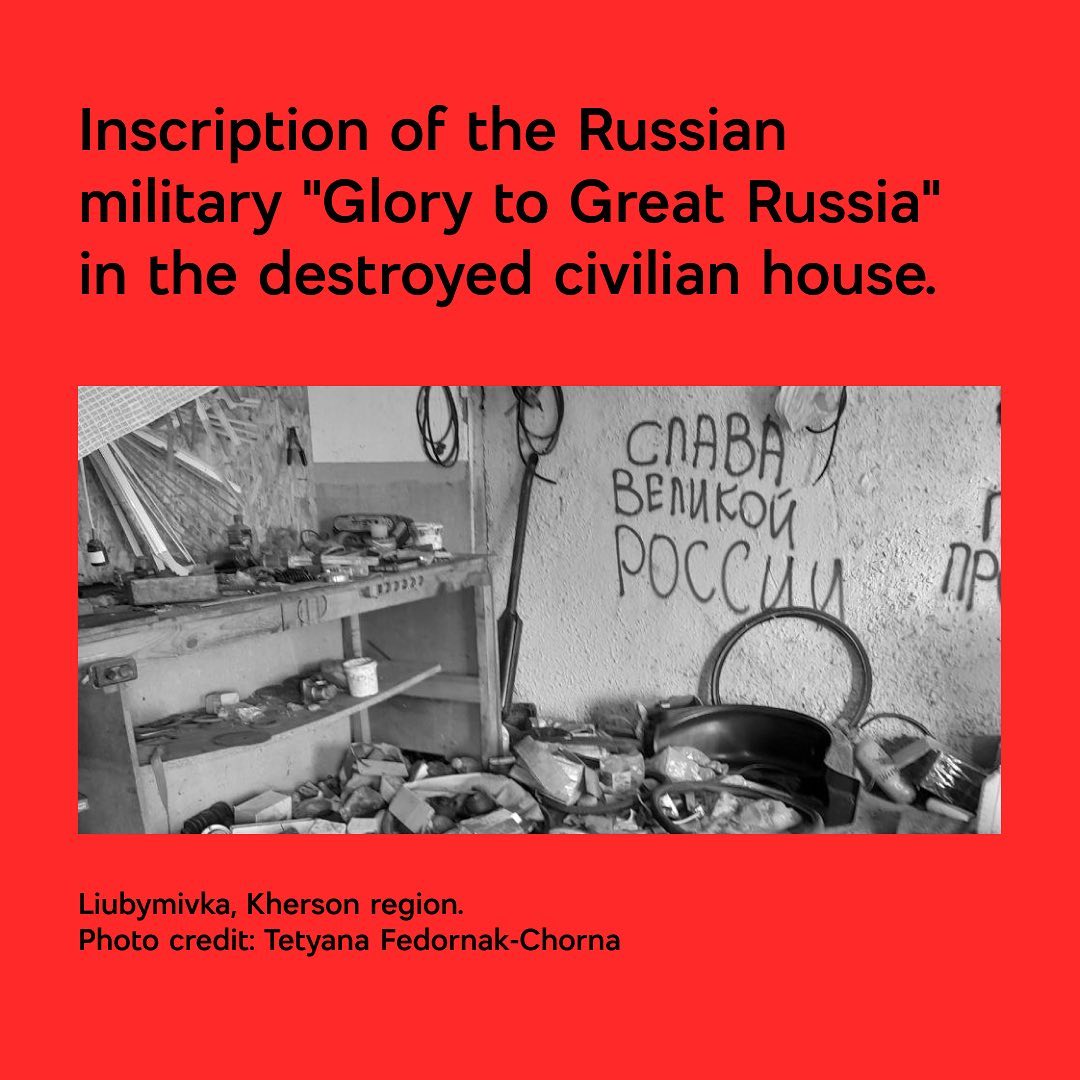

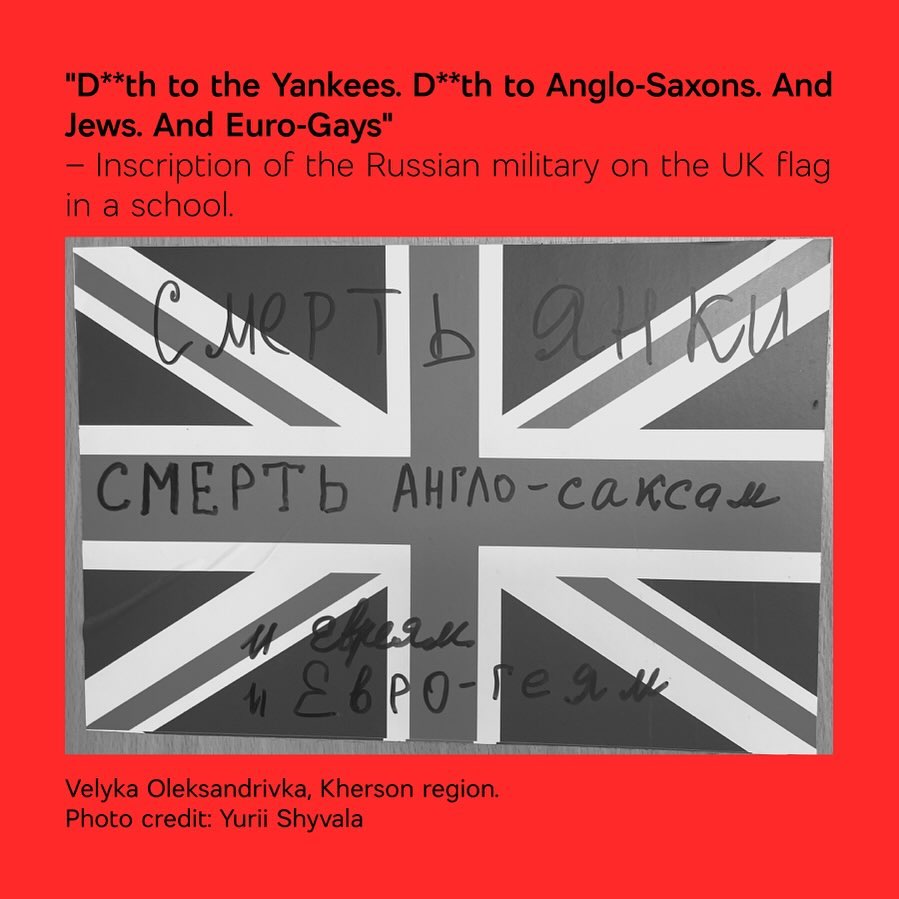

Roksolana Makar: Primarily foreigners, because the archive seems to me to be an opportunity to show the real Russian culture that has come to our country and to demonstrate this ideology through concrete artefacts. In other words, in addition to its research potential, our archive is also an effective means of communicating about the war.

Anastasiia Olexii: Yes, in particular we want to show the graffiti to a Western audience that tolerates Russia and Russian culture, the liberal rhetoric of some good Russians – to show that it’s not just Putin, that it’s not some elite, but a lot of Russian soldiers, and that these are really their thoughts that they leave behind when they come to a foreign country to kill people. Most of our requests for interviews have also come from Western media.

Valeriia Buradzhyieva: And what about the perception of the project of Ukrainians themselves? I have read that at a certain point, there were conflicting perceptions on the rationale behind archiving the graffiti because there were those who did not understand how it was possible to ’memorialise this dirt’.

Anastasiia Olexii: Yes, that happened when we were thinking about how we should communicate the project. It was mainly comments from intellectuals and philosophers who said that graffiti can be found in public toilets as well and questioned if they also needed to be archived and researched? It surprised me, I saw in it a denial of reality. Then I understood it as inevitable. It seems to me that they were not starting from the professional position of a researcher, but from a personal one. The founder Pavlo Gaidai also received comments in private expressing concerns that this is a sensitive subject. So yes, there were certain difficulties in starting the project. The younger generation was more interested in the project. When the materials of the archive were published, the reaction of the public to the idea of the project was quite positive.

Mariami Gubianuri: Documenting war crimes is a common practice in times of war. Did the people who photographed the people killed in Bucha also do something wrong? Our reality is terrible and we are facing it. We are documenting it, and then we’ll see.

Anastasiia Olexii: I thought the archive might shock because it is quite different from what Mizvukhami did before the full-scale invasion – back then we mainly published translations of philosophical books and held lectures and discussions.

Mariami Gubianuri: But I think there was great honesty in that and an indication of a functioning cultural institution, because culture is not about a pretty picture, but about the life and development of society. And this was the cultural institution’s reaction to the war.

Roksolana Makar: I remember the negative reactions. It was an early phase of the war, and the context was different from today: liberation was progressing very quickly at the time, and there was still hope that this war would not last very long. The graffiti we collected in the Kyiv region at that time were quite ambiguous because the Russian military themselves were confused, but they seemed to have the attitude that they would be warmly welcomed by the Ukrainians they came to ‘liberate’. That is, they had their own illusions. This was reflected in the ‘retreating’ graffiti: there were many excuses, such as ‘we were forced’, ‘it was an order’ among others. Some therefore expressed fears that the publication of these writings would in some way justify the Russian military and harm the interests of Ukraine itself — against the backdrop of the attestation of war crimes committed in Bucha, Hostomel, Borodianka and Irpin.

By the time we published the archive, almost a year had passed since the liberation of the Kyiv region. By that time, the situation in the war was already very different and we had a much larger collection of writings that showed that the Russians were not only not weren’t learning any lessons, but were also becoming increasingly brutal. Since we published the project, there have been no more negative comments, apart from very isolated cases.

Valeriia Buradzhyieva: Did you develop an archiving methodology during the project?

Anastasiia Olexii: We want not only to work with the media, but also to attract people in general to work with this archive, because the main purpose of the archive is to use it. And that has turned out to be one of the most difficult tasks, we really need researchers.

Valeriia Buradzhyieva: I have been thinking about this. The graffiti is so visually striking and expressive in itself that it seems difficult to talk about it.

Mariami Gubianuri: From the experience of discussing possible collaborations, we realised that the same occurrence repeatedly happened when working in the archive: you want to do something with the graffiti, but at some point, maybe people get scared – there’s a feeling that you are participating in something not very pleasant. And this moment is interesting to me, I would like to work on it — to find the triggering moments and figure out the context which leads to that trigger.

Anastasiia Olexii: I believe that graffiti should be treated like historical documents— in the archiving process a neutral approach is easier to handle because you don’t perceive them so emotionally. They exist and this is a fact, and you work from there. When archiving, we recorded the dates the photos were taken and, where possible, the context given by eyewitnesses. For example, after the occupation, a woman found a metal breastplate with the Russians’ markings near her house because they had been living in trenches in her garden.

When the archive was opened and we began an Instagram, Roksolana Makar began to translate the graffiti. In the process of translation she discovered a lot surrounding the context of these signatures: verses of a song associated with the Wagner mercenary group were quoted along with some obscure references to Russian popular culture.

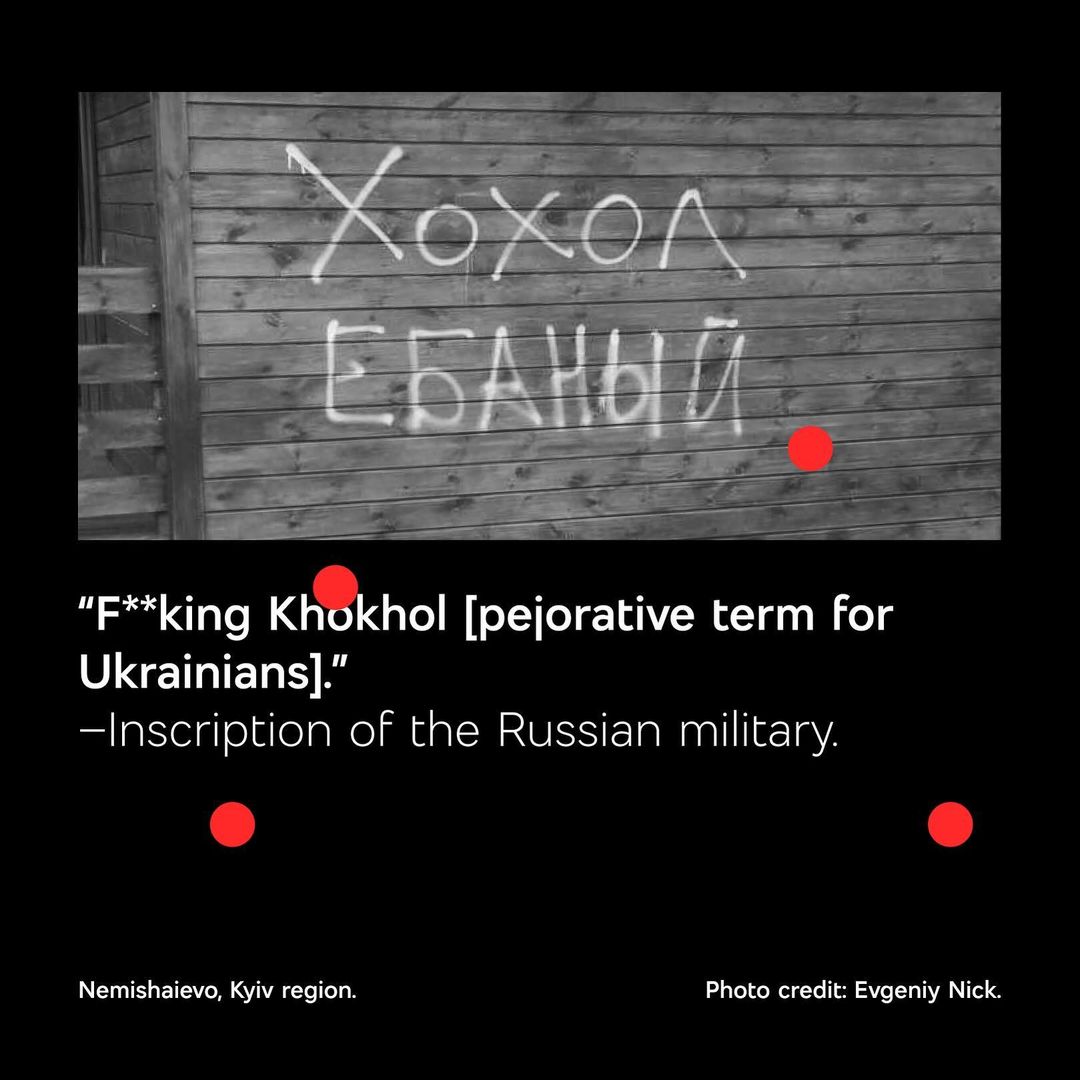

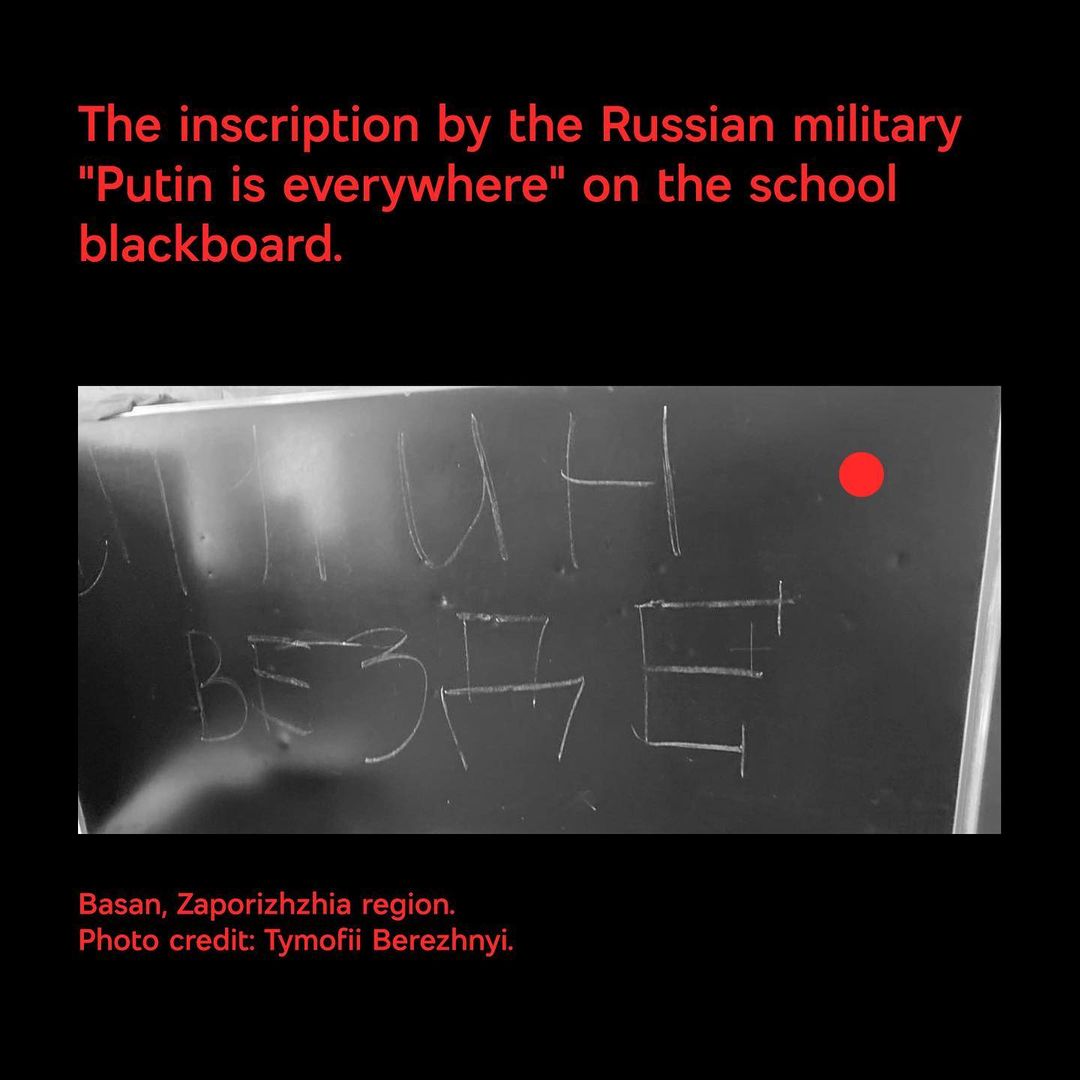

Roksolana Makar: We have tried to categorise the graffiti. The categories include Zs and Vs [2], markings on civilian cars, quotes from Russian popular culture or Russian literature, threats, and vandalism such as ‘Vasya was here’. It is true that in the first month of the war the character of the graffiti was rather confused. As the war has gone on, the graffiti has taken on a more explicitly genocidal colouring, for example in the increased use of of derogatory language like ‘khokhols’ and ‘ukrops’ [3]. There is a whole collection of vandalism about the Second World War, in which this war is actively compared with the present one — graffiti referencing the ‘great war’ and ‘liberators’ [4].

Anastasiia Olexii: We try to provide an interpretation for foreign users, as this graffiti very often contains cultural nuances that they might not understand. For example, the graffiti sometimes refers to Russian memes. Often our audience provides us with additional context. For example, one piece of vandalism says ‘it’s not considered a war crime if you had fun’. This was circulating on the Internet even before the full-scale invasion. Someone posted a photo of it on Twitter, and people started commenting on it and saying, ‘oh, that’s from such and such a meme’. We hadn’t known about the meme beforehand. It’s scary that this genocidal phrase is a meme, a part of Russian popular culture.

Mariami Gubianuri: In fact, some of the overstated, kitsch graffiti did not bear any relation at all to the way that the Russians actually fight, especially not the way they fought in the Kyiv campaign. There is a big difference between what they proclaimed and the reality. I do not think they were having fun during the battle for Kyiv, as they claim in that piece of graffiti. This is the same as repeating the catchphrases of patsantchiki [5]… I remember there were popular groups in Vkontakte [6] which also referenced the same quotes.

Valeriia Buradzhyieva: I also thought of these public pages in Vkontakte when I read some of the writings. Indeed, sometimes the graffiti reads like meaningless, mindless reposts from there — it seems that they do not mean what they write, and instead are just repeating some scary mantra.

Anastasiia Olexii: Yes, or pretentious, kitsch poems.

Mariami Gubianuri: Yes, you could publish a whole collection of those poems…

Anastasiia Olexii: They have already released something similar ‘in support of the SVO’ [7]. The poems in that collection are very similar to the writings that we have archived. When I read it, it felt like both were written by the same people.

Valeriia Buradzhyieva: Have you tried to investigate the continuity of the phenomenon in history? Or compare the Russians’ graffiti with that of other invaders?

Anastasiia Olexii: There was an idea to make publications drawing parallels with the Nazi troops, but such a comparison felt inappropriate to us. Firstly, we do not want to compare tragedies, and secondly, to us it seems like a manipulative comparison. However, I have found graffiti from the Soviet military, so yes, you can say that there is a certain consistency. This topic should be studied more.

Mariami Gubianuri: My father is Georgian, he lived through the war in 1993, and I was in Georgia in 2008 — I grew up with an understanding of what Russia is and the narratives it carries, so this vandalism was not a new discovery for me, I was not surprised. The graffiti from this war is just a confirmation for me of what I already knew, which has been reality in Georgia for a long time.

For me, all the graffiti in the archive is equally cynical. When the Russian soldiers came to our country, they saw the conditions in which we live and the values that guide us. They saw our army, our resistance and began to be afraid because they saw that we are different, that we are not like them: everything they were told was not true, but they can’t just admit that they were wrong. Russians cannot accept the Other, and so they want to destroy the Other because they are afraid of it: it reminds them of their folly, of their naïve belief that they can just come and take what does not belong to them. That is to say, the Ukrainians become witnesses to their baseness. This fear makes them want to destroy even more than they already have.

Valeriia Buradzhyieva: When I think of Wall Evidence, Zhanna Kadyrova’s work from her solo exhibition Flight Trajectories at the PinchukArtCentre, a cut piece of asphalt from Irpin, hit by a Russian shell, comes to my mind. Of course, I was also thinking about the Berlin Wall and the memorial museum Territory of Terror, which stores artefacts of totalitarian regimes. Have you thought of vandalised walls as found objects, telltale artefacts that can be exhibited?

Anastasiia Olexii: As a rule, this graffiti was left in places where various terrible things had happened — that in itself is a question of ethics. Indeed, one would not want to inadvertently fetishise the graffiti by placing it in a white cube. For the exhibition OBSERVE THIS MOMENT – HOW IT CONVULSES at the Arsenal Gallery in Białystok (Poland), we thought about how to display the graffiti and decided to showcase it outside the exhibition space. Perhaps my feeling this way is due to the confusion caused by the public’s initial reaction to the idea of the project. And perhaps I also have my own reservations and boundaries about such a display.

Mariami Gubianuri: I agree that we must not focus too much on any one particular piece of graffiti. We tend to perceive the graffiti as a mass of something, and so I do not think we want to exhibit just any one of them. I also think this is why our Instagram works well as a platform for display, despite the fact that some graffiti cannot be translated and remain incomprehensible to foreigners. For me, the significance lies precisely in the fact that the Russians themselves left these markings alongside their bloody crimes.

Roksolana Makar: I agree, that’s why we insist on the archival approach. As for the preservation of the walls, the originals, we have not yet thought about it objectively. It is possible to do, but here too the same questions arise: what kind of graffiti ought to be preserved and in what context should it be presented? Perhaps it is possible as an exhibit at the Territory of Terror. Nobody wants to have such a memorial in their home or even in their city. That’s why we archive these signatures — so that they can be erased.

The visual materials are prepared by the team of Wall Evidence. Wall Evidence Instagram.

Anastasia Oleksii

An art critic and cultural project manager. She was born in Uzhgorod, and has been working in Kyiv at Mizhvukhamy since 2021, where she is engaged in the implementation of research and cultural and artistic projects. Since 2022, she has been a member of the Ukrainian Heritage Monitoring Lab initiative for documenting and preserving cultural heritage. She is the founder and manager of the ‘Wall Evidence’ project.

Mariami Gubianuri

A journalist and copywriter from Kyiv. She has a bachelor's degree in Religious Studies from Taras Shevchenko Kyiv National University. In 2023, she joined the 'Wall Evidence' project in a communications role.

Roksolana Makar

An art critic, author and researcher from Kyiv. Since 2022, her work has focused on documenting the consequences of a full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. She works at the Ukrainian Heritage Monitoring Lab, participates in the research group of the Raphael Lemkin Society, and heads the content direction of the 'Wall Evidence' archive.

Published 29 April 2024

The conversation is prepared within the Erasing and Recalling project supported as part of the (re)connection UA 2023/24 programme, which is implemented by the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) NGO and the Ukrainian Emergency Art Fund (UEAF) in partnership with UNESCO and funded through the UNESCO Heritage Emergency Fund.

- Kadyrovites are military forces or paramilitary units loyal to Ramzan Kadyrov, the Head of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria within the Russian Federation (the lands of the Nokhchi people occupied by Russia). These soldiers are often members of the security forces like Chechen Special Forces known as the ‘Kadyrov Guards.’

2. The Latin letters Z and V that came to symbolise the Russian army during the invasion of Ukraine, as they are often found on Russian military equipment. It is assumed that these letters indicate the military district from which an item of equipment originates from— ‘zapad’ (Russian for west) or ‘vostok’ (Russian for east). You can read more about Russian war symbolism in an article by Ukraїner https://www.ukrainer.net/absurdity-of-russia-symbolism/.

3. Russian pejoratives for ‘Ukrainians’.

4. ‘The Great Victory’ refers to the victory of the Allies in the Second World War which is considered by Russia to be an exceptional achievement of the Soviet Union and Russia in particular and does not discuss in detail the other members of the Allies. In the ideology of Russian violence against Ukraine, this historical event is seen as the heroic period that epitomises the power of the Soviet Union and provides the rationale for today’s Russian colonial wars disguised as ‘wars of liberation’, akin to the liberation of Europe from the Nazis.

5. A word used to refer to male members of delinquent subculture in post-Soviet countries who tend to live by the code of honour established within the community, which demands, among other things, respect for brotherhood and justice, although in real life these principles are often subverted by the members themselves.

6. A popular Russian social network with headquarters in Riga, Latvia.

7. The term ‘special military operation’ (also known as ‘special operation’ and abbreviated as ‘SMO’ or ‘SVO’ for специальная военная операция) is an official designation utilised by the Russian government and pro-Russian sources to denote the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This term is widely perceived as a euphemism intended to downplay and obscure the true nature of the conflict, which is recognised as a full-fledged war initiated by Russia. Additionally, it serves to assert Russian success in the operation regardless of the outcome.