The Drowned Memory

Ukrainian philosopher Volodymyr Yermolenko explores how Russian techniques of memory erasure — from the massive artificial floods that desolate the land's historical signifiers to the looting of museums and imposed ideological commemoration — have trapped Ukrainian identity in a state of 'amputated future'.

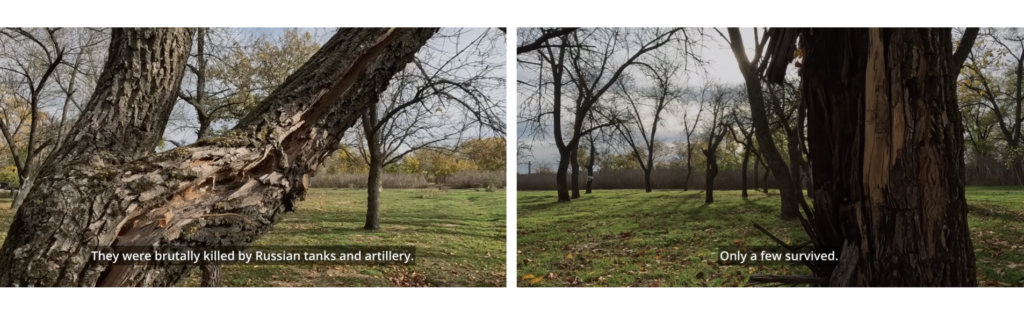

The following stills used in the text are from the movie KHERSON - One year after liberation produced by the UkraineWorld team.

Walking through Kherson’s local history museum feels like walking through a house after a flood. The walls are empty, though you can still see inscriptions designating objects of art or archeological findings. But these objects are gone. They were taken away by someone: a monster, or a hurricane.

You feel as if you are walking through a building, whose residents have suddenly disappeared. Their names might still be on the doors, and you might still be able to find unread letters in the mailboxes – but there is nobody around. They have all gone.

The museum’s director Olha and its senior research specialist Kateryna led us from room to room, from one place of memory to the other.

Here is a room of Scythian gold – one of the treasures of Ukrainian memory. Here is a room of Olvia, an Ancient Greek colony near the seashore, not far away from Mykolaiv. Here is a room of other Ancient Greek colonies in the northern Black Sea region. These rooms are empty now.

Russians occupied Kherson in March 2022. They fled from the Ukrainian army in early November 2022, but before they left the city, they stole its memory. They robbed the Fine Arts Museum (over 10,000 art objects, including paintings of the most famous Ukrainian artists), and they robbed the Local History Museum (it had over 100,000 objects – archeological findings, art objects, testimonies from the past – and a big part of the collection is now gone).

The museum guard, with whom we speak, tells us that the men who came to loot the museum weren’t very sure what to take. They just gathered everything into the large boxes, loaded them into cars, and left.

There is a similar story in the Kherson Fine Arts Museum, located across the street. Over 10,000 works of art have been stolen from here, including paintings by Aivazovskyi, Pymonenko, Kuindzhi and others. A museum worker with whom we spoke had risked her life by claiming to the Russians that the collection had been evacuated. They eventually found it and stole it. They might have shot this woman.

Today these museums are in one of the most abandoned districts of Kherson. It is situated close to the river, on the other side of which stand the Russians. Approaching the river is dangerous. The streets are almost deserted. As we get out of the car which we had brought to the soldiers in Kherson, a drone flies above us towards the river. We don’t know whose drone this is. We film a destroyed children’s library. We feel lonely.

Proximity to the river has usually been a source of life. It has always been beneficial to be close to the major travel and trading sources.

Now proximity to the Dnipro River (the major river of Ukraine) in Kherson is dangerous. You can be shot by a Russian sniper on the other side of the river, or you can be killed by an artillery strike. The Russians are so close that they might be able to see you through a sniper scope. For them, you are a random target. A geometrical object with no memory, with no past and no future.

The «Russian world», whose violent expansion we witness, doesn’t think about the past or the future. It lives in the eternal presence of violence. It truly believes that violence should not be remembered, because it should not be so it can never receive redemption. Crime can go on only if you create a reality of amnesia. Evil can win only if everybody forgets about it. It reigns in oblivion.

It can repeat itself as soon as people forget.

***

Humans are journeys. They are journeys in time. The question ‘Where do you come from?’ does not only refer to geography, it also refers to chronography. We come from a certain time, and are married to a certain place. We are children of our time and place.

Some philosophies tried to negate this dependence. They worried about our sick dependency on time. Time can indeed be our prison. Our roots can be too strong to let us go further. But cutting the roots is an illusion. The roots will bleed, will remind us that they’re there, and will seek revenge.

The Soviet era was, among others things, an era of wars with the past, and with roots. It thought that the industrial metaphor would replace the botanic one. It thought human beings were machines, not trees. Machines should be repaired when they are broken. They should be fed with fuel, not food. Food should give them energy, not taste or aesthetics. Sometimes they should be allowed to forget themselves: allowed to drink some alcohol after a busy working day.

Humans-machines were placed by the Soviet empire into large boxes called houses, multi-storey reservoirs for workers. As a box for machines, these buildings should not be beautiful, the system said. Nor should they be specifically ugly. They should have no aesthetics at all. They should be beyond any aesthetic question. Beyond “beautiful” or “sublime”, or even “interesting”.

These boxes should be put in other boxes, called “spalnyi raion”: a district where you come to sleep. A district which does not allow any other life – promenade, music, theatre, university, – only rest after a hard working day.

Humans are machines, they have been put into boxes; they are not trees, they don’t have roots. Therefore, their past should be simplified, or erased. You are not interested in the past of the machines. If machines are too old, you throw them away.

This is what Russian communism did with memory. It said memory is a luxury. It said memory is a symptom of “bourgeois nationalism”.

The botanical side of humans – their rootedness, their origins, their points of departure – were reduced by this regime to a very low set of stereotypes. Or intentionally exterminated.

Communism’s key metaphor was a metaphor of fire and steel. Steel should be “tempered” in the fire. Communism should be hard, it should oppose the ‘soft’ loose black earth (chornozem) of peasants, or the ‘airy’ aesthetics of the old aristocracy.

Communism had to conquer the earth and water. It conquered the earth by killing millions of peasants, building industrial cities, and changing the names of the land, regions, streets, and towns. By making cities speak another language. By cutting the roots.

It conquered water by conquering rivers. By determining how the river should flow. By constructing dams, for example. Dams were needed for the hydropower plants, or the nuclear ones. They changed the natural flow of water. They changed the natural borders of rivers. They took water from one place and put it into another. Communism wanted to be demiurgical.

Earth and water are where spirits live. Which means: our memories, and spirits of the dead. Lesia Ukrainka, the great Ukrainian writer, knew it well when she put her spirits into the forest, the guardians of the world, and of its memory.

One of the spirits of her ‘Forest Song’ was ‘The One Who Breaks Dams’. She probably meant the dams of oblivion.

***

Earth and water keep our time running. Earth is the force of repetition. It makes growth possible, every year. Every year a cherry tree looks the same. And yet, it doesn’t. You can always find something unique. Not like the last time.

Water is the force of non-repetition. You can never enter the river twice, said Heraclitus. Both the river and you have changed. Both are not the same. And yet, water circulates, it goes from the body to the body, and it was created 4,5 billion years ago. If water could tell its memories, it would tell us the stories: about Christ, Achilles, Gilgamesh, and, of course, Noah.

One more thing: rivers keep their names. We connect with our grandfathers and grandmothers through the names of the rivers they have entered. So, not only you but your grandsons and granddaughters will go into the same river. If they survive.

Earth and water form this strange duet: non-repetitive repetition. Repetitive non-repetition. A variation in which we always recognize something we already know – and yet it always brings something new.

But communism, remember, wanted to conquer both water and earth. It wanted to make everything planned. It wanted to subdue everything to power and violence.

***

Water as memory: this is the key metaphor of Sofia Andrukhovych’s novel “Amadoka”.

One of the best recent Ukrainian novels, it is founded upon a metaphor of the lake of memory. Amadoka is a lake that existed in Western Ukraine during the Middle Ages (according to geographers – or mythographers – of that time), but has now disappeared. The stories told by Sofia are the stories of this disappearance. These are the stories of how people erase their past; how time and memory are ejected from the places where they lived, turning these places into silent and blind “res extensa”, without a soul.

The water here is a reservoir of memory. The lake is its home, a memory with borders and an ecosystem. A memory that creates rules for what exists – and what is told. Destruction of this memory is a destruction of the very life forms that have populated this lake – this space and time, this geography and chronography. The lake evaporates, and the whole world disappears.

Sofia tells us about these worlds. About a world of Jewish culture and Chassidism in the Western and Central Ukraine – that of Baal Shem Tov. A world of the Ukrainian baroque, searching for a harmony that was cut in pieces by the Russian empire, but still existing in the dreams and practices of wise men like Skovoroda. A world of the wounded aesthetics of the borderlands, like that of Pinsel. A world of erased Ukrainian culture of the 1920s, like that of Mykola Zerov. A world of a major character in the novel: a man who lost his face in the war started by Russia against Ukraine.

These are all fragments of that lake Amadoka. This lake will never return. You can only use archeology to find its traces. You can find skeletons of creatures that populated it in the sand that still keeps the memory of something that everybody else forgot.

Water evaporates. Memory remains confined in traces. It was convicted, it had a prison sentence, it was sent to jail for years.

Memory was sent to Gulag.

***

Yet in Kherson, you are facing something different. In June 2023 Russians blew up the dam on Dnipro River. Back in the 1950s construction of this dam – and of the hydropower plant itself – created an artificial Kakhovka water reservoir. Six dams on the Dnipro River, constructed during Soviet times, – in Kyiv, Kaniv, Kremenchuk, Kamianske, Zaporizhzhia, and Kakhovka – have transformed the geography of the Dnipro Basin – and its history. They have created new lakes, which didn’t exist before. They have destroyed dozens of villages and ecosystems, drowning them’

You can take this metaphor and say that they have created artificial lakes of memory. And these lakes have covered all the previous history – for example, the unique Ukrainian Cossack history, and its Velykyi Luh1 – in water.

The blowing up of the Kakhovka dam reduced the level of water in some places whilst increasing it in others. We walked in Korabel and Ostriv districts in Kherson, where water reached the second floors of the buildings and remained there for several weeks. At that time, cars were replaced with boats. People turned into amphibians.

But this flood happened before, too.

It happened when Kyiv Dam, Zaporizhzhia Dam, Kakhovka Dam and all the others were created. They caused a flood that covered the past. They caused memory to drown. They turned the roots into a dead body underwater.

In this case, memory disappeared not because it evaporated but because it was drowned. Because a huge amount of something else came and put it underwater. And memory suffocated. It couldn’t breathe. It lacked oxygen.

The politics of memory during the Soviet times is this: not the gradual evaporation of a lake of memory, but the fast suffocation of memory in the artificial lake of forgetfulness and amnesia.

In this war the Russians have repeated this crime. They have caused a flood again. The flood was several meters deep; it killed people and animals. But the water has also vanished from those places where it appeared when this artificial lake was created. And this second crime – the double crime, the twin crime – the destruction of the lake after you first created it, is a crime that in some way erases the previous one. It brings back the lost history. It will not revive the past, but it can show that here, this past was killed. Here it lacked the oxygen it needed to breathe.

In Zaporizhzhia we go to the famous Khortytsia island. It is a place where Cossacks had their Sich. The Sich was created ‘behind the rapids’; Za porohamy. And therefore it is called Zaporizhzhia, and the Cossacks are called Zaporizhzhian Cossacks.

The dams constructed on the Dnipro River covered these rapids in water. They covered Cossack history in water too.

Current Russian crimes uncover the crimes of the past. We look at the Dnipro River from Khortytsia and we see these rapids again. The explosion of the Kakhovka dam increased water levels in Kherson but decreased them in Zaporizhzhia. In many places, the ‘lake’ has gone. In many aspects, the lake of oblivion has gone too.

What will emerge in its place? It might be a revival of the Velykyi Luh, and of the Cossack glory. Or it might be a desert. Both are possible.

***

Commemoration is our attempt to delay death. We know both death and forgetting are inevitable, but commemorating forces the absolute death (which is oblivion) to wait. It does not let it come too soon. Through having memory, we extend life a little bit.

You cannot say that communism didn’t remember. It did have memory, but this memory was highly standardised. Its memory could not surprise. It was not unpredictable. Lenin Streets in every city and every village. Gorky Parks in every big city. Pushkin Streets, October Squares, Komintern Avenues. It was always the same.

In a city museum in Zaporizhzhia our guide shows us the map of Soviet Zaporizhzhia compared to the map of other Soviet cities in Russia and Belarus. The ‘skeletons’ of the city, the key names of the key streets, are the same.

What we love about our past is that it is unpredictable: it is always open to new facts and interpretations. Even our personal past is such: we are surprised when we find old pictures of ourselves or diaries written when we were at school.

We love our past because it can surprise us. We also love it because we can recognize ourselves in it. Knowledge is memory, said Plato: we don’t really get to know something, we just recollect what we knew before. But the reverse is also true: memory is knowledge. Looking at the past, if it is done right, enriches our knowledge. We learn something not only about the past, but about the present and about the future.

***

Wise people say that alternative history is a bad idea. You cannot think ‘what would happen if…’. History is what has happened – and if it did happen, then it’s useless to think that it could have happened otherwise.

Yet, if we identify what has happened with what had to happen, we admit that ‘the winner takes it all’ and violence (which is usually the cause of our history) has been justified.

In Ukraine, this thinking about alternative history makes sense. Ukrainian history is a story of amputated futures, of plans which were not realised, of ideas that did not become novels, philosophy treaties or art works, of melodies that were never written down and never performed. So we might start thinking about what would have happened if they had survived.

Just think about some names.

Valerian Pidmohylnyi, a Ukrainian writer and translator (translated Diderot, Flaubert, Hugo, Maupassant etc). Wrote his famous novel Misto (The City) when he was 27. Arrested in 1934 (aged 33), and executed in 1937 (aged 36).

Hryhorii Kosynka, a Ukrainian writer and translator. Arrested and executed in 1934 (aged 35).

Yevhen Pluzhnyk, a Ukrainian poet. Arrested in 1934, died in the camps from tuberculosis. Aged 38.

Mykola Khvylovyi, a Ukrainian writer, a leading voice of his generation. Killed himself in 1933, protesting the arrests of his fellow writers. Aged 40.

Ostap Krushelnytskyi, a Ukrainian cinema critic. Arrested in 1934 (aged 20) and killed in 1937 (aged 24), together with other members of the Krushelnytskyi family.

These are just a few names. There are hundreds more. All these people were at the beginning of their lives. They had only just begun. You can imagine what they could have acheived had they been allowed to live their full lives.

In ‘The Master of the Ship’, one of the most brilliant Ukrainian novels, Yurii Yanovskyi tells a story of an old writer who, through recollections of his past, describes his youth. The paradox is that it is a novel written by a young writer. It is double time travel: an old writer who remembers his youth, and a young writer who imagines his old age. It’s a novel of a young writer imagining his older version who recollects how he was a young writer.

Yet, for the Ukrainian context, it is almost an impossible experience.

An amputated future, a tomorrow that will never happen, ‘development’ as a banned word. It happened in the 19th century, it happened in the 20th century, it is happening today.

There are many definitions of happiness but for me one thing is clear: you cannot be happy without a future. The absence of a future is what causes sadness. We are too focused on the time ahead of us. We are too focused on our hopes.

The Ukrainian memory is often a memory of an unrealized future, of an amputated hope. It is a memory about the past which was not allowed to become the future.

Today’s Russian war against Ukraine is a repetition of this. It’s the demons of the past coming back again. It’s the vicious circle that is so hard – and so necessary – to break.

Will we be able to break it this time?

The text is edited by Ada Wordsworth.

Dr. Volodymyr Yermolenko a Ukrainian philosopher, journalist and writer. President of PEN Ukraine. Doctor of political studies (France), PhD in philosophy (kandydat nauk, Ukraine). Analytics director at Internews Ukraine, one of the biggest and oldest Ukrainian media NGOs. Chief editor of UkraineWorld.org, a multimedia project in English about Ukraine. Associate professor at Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. Book writer (non-fiction and fiction), winner of Myroslav Popovych Prize (2021), Petro Mohyla Prize (2021), Yurii Sheveliov Prize (2018), Book of the Year prize in Ukraine (2018, 2015) and others. Head of board of International Renaissance Foundation (OSI Network). Public lecturer. Expert in information analysis and media literacy; architect and trainer at several media literacy projects within the activity of Internews Ukraine and UkraineWorld. Co-founder and author of podcasts Kult:Podcast (in Ukrainian) and Explaining Ukraine (in English). Anchorman of TV programmes Ukraina Rozumna and Hromadske.Svit at Hromadske.ua (2016-2020). Author of numerous articles in international and Ukrainian media. Published in The Economist, Le Monde, Financial Times, New York Times, Newsweek, gave numerous comments to BBC, CNN, Al Jazeera, France 24 etc. His texts and interviews have been published in Ukrainian, English, French, German, Polish, Italian, Russian, Dutch, Norwegian, Czech, Greek, Chinese and others. Father of three daughters.

Published 28 March 2024

The text is prepared within the Erasing and Recalling project supported as part of the (re)connection UA 2023/24 programme, which is implemented by the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) NGO and the Ukrainian Emergency Art Fund (UEAF) in partnership with UNESCO and funded through the UNESCO Heritage Emergency Fund.

- Velykyi Luh (the Great Meadow) is the historical name for an area within the Dnipro floodplains. It served as the home for the Zaporizhzhian Sich and four other Siches — semi-autonomous polities of Cossacks that existed from the 16th to the 18th centuries. It was a habitat for unique flora and fauna until it was submerged by the Kakhovka Reservoir in 1956.